Glenn Miller And The Army Air Force Band Of 1943-44: The Major Goes Out At The Top Of His Game

In the world of the pre-WWII big bands, one popular name that was not synonymous with jazz was Glenn Miller. Miller, who led the most popular band in America in the years leading up to the war, was usually categorized as a “sweet band”, as opposed to a “hot band”. There was, however, a brief era when a Miller-led band could drive as hard and swing as relentlessly as the best of them. That was when Miller led the U.S. Army Air Force Band in 1943-44. It is a band that should be better known today than it is.

In my forays into old-school jazz music here, one big name has been conspicuously absent – Glenn Miller. This has mainly because Miller’s music never earned the jazz cred of several other contemporary bandleaders. I did feature one Miller recording, in a comparison with Benny Goodman’s treatment of the same song – “String of Pearls”. I don’t think I hid my opinion very well, which was that the more obscure Goodman version was superior. Whether or not he needs it, Glenn Miller’s reputation gets some rehabilitation on these pages today.

Miller’s story is an interesting one. He was a contemporary of other top names like Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Tommy Dorsey, who toiled away in relative obscurity in the late 1920’s and early 30’s before hitting it big on his own. He was a bandmate of Goodman in the Ben Pollack Orchestra around 1930-31, but soon realized that his abilities on the trombone were not all they might have been. By the early 30’s Miller migrated into and out of multiple well-known bands, mostly as a writer/arranger before launching his own band in 1937.

That first band soon flamed out, but a second effort in 1938 was better received and by 1939 Miller was leading one of the most popular bands in the country. In the four years of 1939-42, Miller racked up 16 number-one records and 69 records that were top-ten hits. For perspective, this was more than either Elvis or the Beatles churned out during their respective careers. And if you are in the mood for some trivia, his 1941 recording of Chattanooga Choo-Choo was the first million seller commemorated with an actual golden disc.

Musically, the Miller Band was not so much of a jazz band, but one that had an unfailing feel for the pulse of American listeners and dancers. Miller was everywhere in those days – churning out records, playing packed ballrooms and appearing frequently on his radio show sponsored by Chesterfield cigarettes. So it was no small thing in 1942 when he gave it all up (including weekly earnings that would today be in the range of $350,000) to enlist in the military in the aftermath of the December, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

Major Miller soon found himself in charge of a tremendous outfit that numbered in excess of 45 members (some sources put the figure as high as 51), including singers and a large string section. By mid 1943 this new Miller band was recording V-Discs (records distributed among the armed forces), transcription discs that would replay shows over the radio and lots of live performances for military personnel in England.

Band personnel included some notable players, like 20-year-old Mel Powell who played piano and had been a creative force in Benny Goodman’s late pre-war band. The drummer was the dynamic Ray McKinley who had led his own band, and who provided a solid base for a really good rhythm section. Two pre-war Miller alums were bass player Herman “Trigger” Alpert, who had been a real upgrade for the Miller civilian band after he joined in late 1940. Alpert was joined by another key transfer – the ace arranger Jerry Gray, who had been responsible for writing more than his share of those many Miller pre-war hits. We must note that Alpert was a native of Indianapolis, your scribe’s adopted home town.

The AAF unit was also blessed with singers who were far better than any who had that role in Miller’s civilian band. In addition to the close harmony unit called “The Crew Chiefs”, both Tony Martin and Johnny Desmond got time before the mic.

* * *

One of the last L.Ps I bought before I made the transition into music on CDs was a two-record album of music recorded by Miller’s AAF band. I didn’t spend much time with it because life was starting to get busy and I didn’t have time for sitting around listening to vinyl discs then. But I recently got my hands on that album though a streaming service and have been revisiting it.

One of the things Miller did (which was not all that popular up the chain of command) was to jazz up the music for marching in drills and parades. The old John Phillip Sousa marches were not that popular with the young recruits, but things like Miller’s St. Louis Blues March really got the troops moving in a way that resonated with them. Co-written by Jerry Gray, Ray McKinley and the all-but-forgotten Perry Burgett, this is probably the best known of the many recordings of Miller’s AAF band. Many re-releases shorten this piece to fit on a typical record side of the era, but this is the uncut version that includes some excellent solo performances.

Most of what has been preserved from this band were transcription discs (we described those in more detail here) which were used for radio broadcasts. One such recording is an obscure piece called “Tail End Charlie”. Miller himself had once said that his band did not play jazz, but this recording proves that with the right players, jazz (and good jazz, at that) could come from a Miller-led outfit.

Why the difference? Part of it was that most of these players were a decade younger than most of Miller’s pre-war personnel, and they played like it. But more importantly, the rhythm section of Ray McKinley, Trigger Alpert and Mel Powell really gelled in a way found in only the very best big bands. In the last thirty seconds or so of “Tail End Charlie” when the band gets quiet, you can hear those three guys hard at work laying down a highly contagious rhythm that infected everyone in the band.

Not everything they played was straight-up jazz. One really ambitious piece was nearly 6-minute-long re-imagining of “Holiday For Strings” by David Rose. This was Rose’s first major contribution to popular music, first released in 1942 and that became a big hit when it was re-released in 1944 during the musician’s union recording strike.

This piece – a great chance for Miller to showcase that big string section – is like a mini-concerto that begins with a relaxed jazz treatment, before changing into a fairly faithful rendition of Rose’s original (which the curious can find here). But then Miller slows the pace way down with both a section for his signature saxophone-clarinet sound and then a lush string follow up that concludes with a poignant violin solo. But then gears shift once again for a brief hard-swinging finale that brings things home. What I find most impressive is that this group could master every one of those disparate styles, never making the listener think that they were trying to do something they weren’t really good at or suited for.

If you are short on time and can listen to only one song of today’s sampling, it simply has to be this last one – “Flying Home”. This song was first recorded in 1939 by Benny Goodman’s quartet and featured Lionel Hampton. Hampton also recorded it with his own big band in 1942, with a long solo by young tenor sax player Illinois Jacquet. My own opinion is that Miller’s AAF version of “Flying Home” may be the best I have ever heard.

Both the Jerry Gray arrangement and the rhythm section drive hard from beginning to end on what might be the best thing a Miller-led band ever put on a record. There were some top-tier big jazz bands (both pre and post war) that made records as good as this, but I am not sure any are objectively better.

Most of this music was not released to the public until the mid 1950’s. The collection I listened to contained a wide range, including several ballads of the kind Miller was always good with, as well as Miller’s signature medleys of “something old, something new, something borrowed and something blue.” There is a lot of music on this collection, and pretty much all of it is really good – like a version of “The G.I. Jive” sung by drummer Ray McKinley and The Crew Chiefs (found here) if you are craving more than the four songs featured above.

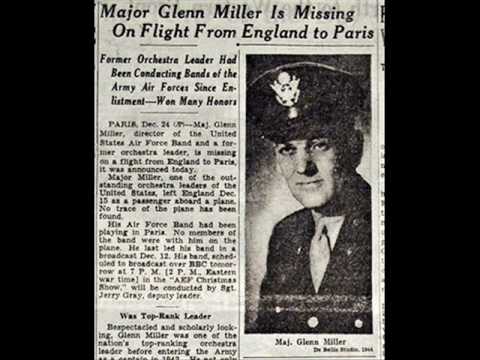

The sad ending to this story is that Miller’s band was to fly from England to France in December of 1944. Miller wanted to get there before the rest of the band and finagled his way onto a December 15th flight with a couple of other officers. Tragically, that flight never made it to the other side of the English Channel. The plane was not located and Miller was finally declared dead on December 16, 1945. There have been lots of theories about what happened, but the consensus seems to be that the plane was flying low and was brought down by ice buildups on either the wings or in the fuel system because of the cold, wet conditions.

Jerry Gray and Ray McKinley co-led the band after Miller’s death, and both went on to other successes after the war. Miller’s pre-war band was more-or-less recreated by that bend’s lead sax player, Tex Beneke, who had quite a bit of success. However, Beneke resurrected a pre-war Miller band that seemed unaffected by the kind of music Miller was playing in his AAF unit. It is intriguing to wonder what direction Miller might have taken after the war was over had he lived to muster out of the army and re-start his civillian career. My own bet is that his band would have been far better than the one Beneke led in Miller’s name.

Miller’s other musical legacy is in the Army/Air Force. Miller’s group spawned the jazz organization within the Air Force, called “The Airmen Of Note”, a group that continues to play jazz gigs wherever it can up to the present day.

I listened to a lot of Miller when I first started investigating big band jazz, and soon tired of what seemed to be a formulaic group of modestly talented soloists. The ever-acerbic bandleader Artie Shaw once described Miller as “a nice guy”, but then quipped how it would have been better if Miller had lived and his music had died. I have revisited my opinions on Miller over the years, and have concluded that Miller’s records of 1941-42 were of far better quality than his earlier ones and are worth a listen. But for my money as one who loves old-time jazz, it is Miller’s recordings with his Army Air Force band of 1943-44 that gave us Glenn Miller at his very best.

If Glenn Miller had lived, there’s no telling what the band would have turned into, and what “new” music would have been on offer. With his death, poor Tex Beneke was at the head of a “tribute band”, playing the “hits”, and carried it out in perpetuity. If I’m not mistaken, he was active until the early ’90’s, and could be seen on television variety shows, well into my own thirties.

It’s hard to understand how Millers band was so popular across the spectrum, when radio “narrow-casting” in my generation meant you could basically listen to country and western, or jazz, or whatever by selecting the radio station that was concentrating on that music. My parents, who listened to opera, classical, and only some pop and jazz; were familiar with and listened to Miller during the war years, and I think most people did, as well as his music during the run up to the war. My Mom started listening to pop and rock in her old age, and went to concerts from ZZ Top and Rod Stewart in her 80’s, go figure! My father also appreciated Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and loved group singers like The Ink Spots, having himself sung in the famed Purdue Glee Club.

I mention the above because it seems like I know people that can’t stop listening to whatever music was going on in their teens and early 20’s. The radio spectrum is full of AOR radio stations playing, way overplayed rock music from fifty years ago. Bob Seger and Fleetwood Mac, please, please be gone! But, my parents always considered Glenn Miller “old music” and weren’t particularly interested in listening to it over and over again. My city has an excellent college radio station playing a Big Band show every Sunday morning and I tried to set it up for them to listen to, and they were only mildly interested, and didn’t particularly care to keep listening to it. When the Miller band helmed by Beneke would appear on TV shows, my parents wouldn’t particularly watch it and might change the channel and hunt around. It seems like I was more interested in Glenn Miller than they were. Artie Shaw’s take was interesting, showing maybe wildly popular music isn’t necessarily respected music. I actually love the movie clips of the Miller Band that appear on Youtube and watch them fairly frequently.

Wouldn’t be amiss to look at Lawerence Welk’s career, one of the last “sweet” traveling bands, and think if Glenn had lived, we might be watching him on PBS as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My parents were too young to have been Miller fans, but he was kind of my gateway drug into jazz when I borrowed an album from a friend’s house.

I always compared Lawrence Welk to Guy Lombardo, who also made money hand over fist playing schmaltzy music. Miller’s trajectory would have been interesting. He wasn’t really a good jazz player on the trombone, so would he have been able to keep a band going into the 50s when so many folded for financial reasons. I guess we’ll never know.

LikeLike

I always recommend, even today, that it’s worth a flip by PBS on a Saturday night to see what Welk era band is on! If it’s an old black & white kinescope of the early TV years, you could be surprised, as I was, how hot that band can be! I think the truly terrible “schmaltz” came with the amount of time it was actually on TV. It’s interesting that the mid to late color years of the PBS show, the episodes are almost “schmaltzy-unwatchable”, and there are an amazing amount of guys from the earlier shows that are no longer in the band? Moved On to more jazz oriented situations? Didn’t match the “new direction”? No one ever seems to want to talk about Welk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I know people that can’t stop listening to whatever music was going on in their teens and early 20’s.” This is a widespread phenomenon that has always frustrated me. I listen to music from ALL ERAS, from J.S. Bach up through modern times (not too much modern stuff, but I do find a few recent gems here and there). If you were born in the 1920s, you’re going to like jazz and big band. If you were born in the ’40s-early ’50s, doo-wop rock and roll will dominate your life. Etc., etc. Why do people limit themselves like that? Isn’t good music timeless and universal? It’s like the year you were born FORCES you to like the music you like.

My father (today’s his 90th birthday) was born in 1935. He likes big band, Dixieland, and jazz. He has Glenn Miller records, and I started listening to them, and I like Glenn Miller. Dad graduated high school in ’53, so he “missed” rock and roll, and hated Elvis. Dad’s friend was born a few years later, graduated H.S. in the late ’50s, so he’s totally into rock and roll! So what determines what you like–your personal preference or what you’re exposed to and peer pressure?

Humans are weird.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stephen, there is so much music being created, I cannot understand why people limit themselves to old music from their youth! I get a British music magazine called UNCUT, that includes a CD and a little booklet of new music, and I’ve literally never heard of any of these people or bands, at least not 95% of them, not even on American college radio?

LikeLiked by 1 person

There does tend to be a sort of herd mentality in music, as there is with styles or anything else. Sometimes the herd of 75 (or 200) years ago works in favor of those of us who venture out into the deep water for our music.

LikeLike

Terrific essay. It’s unexpected, in a way, that military bands existed and still exist. But I guess the top brass believe it’s important to try and keep the troops entertained.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! It occurred to me what a great bit of luck it would have been for a young kid in the service to spend his military career on a bandstand and not on some terrible place like the beaches at Normandy. The guy who was a good jazz player could really make out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I recently read this about being in the military: “A military career can offer you the chance to build expertise in a variety of personal and professional skills areas. As you grow as an individual, you’ll gain experience that can help you excel in the Military and beyond.” I suppose that was true for Miller?!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite possibly. There was also the benefit of having a big enough name to get the pick of a really big pool of young musicians who had either enlisted or been drafted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Miller is one of my favorites. I don’t normally think of him in connection with jazz — “Big Band” seems to me like a different style, but maybe that’s just me. I still think that Miller’s “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” absolutely rocks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there is a boundary between straight big band music and big band jazz. I also think that Miller’s AAF band got a lot closer to that boundary (and occasionally crossed it) than the civilian band did.

I agree on Chattanooga Choo Choo. I have heard a live version or two that picks up the tempo, which I think makes it even better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a wealth of information here. I actually learned quite a bit about Glenn Miller from the movie, The Glenn Miller Story, with Jimmy Stewart and June Allyson. Nice selections of music here, and thanks for putting so much into this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That movie suffered from many of the flaws common to vintage biopics, including the way it refuses to let some facts get in the way of a good story. But anything starring Jimmy Stewart is hard to criticize too much.

And thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You put a lot of effort into this post JP … I wish I was more familiar with this genre of music. It’s sad how many musical artists have died in plane accidents over the years, often in Winter (Buddy Holly, Patsy Cline come to mind and I’m sure many others).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Linda. Ricky Nelson is another musical plane crash victim who comes to mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, in the Winter as well. I also thought of Jim Croce, but he was in the Fall. I had just started college and we were in the newspaper staff room, had the radio on and a news flash came on about him and others in his entourage all dead from a plane crash. I really liked his music very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love how our armed forces continue to staff musical ensembles well after the years you’re referring to here. I was reminded of this during the presidential inauguration, when the Naval Academy Glee Club belted out “Battle Hymn of the Republic”. It made me wonder whether the accompanying orchestra was also supplied by the military. I now know a lot more about someone who’s name I was familiar with but not much else – thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I saw The Airmen Of Note at a free lunchtime concert. It was part of a monthly series put on during nice weather by a local venue near my downtown office. They were quite good!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been a Glenn Miller fan since the 1980s when my grandparents played some of his music from their original 78s for me. You’ve helped me see his place in the music pantheon — just good pop. Nothing wrong with that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I would argue that this AAF band pushed (at minimum, and if only occasionally) the boundary between pop and jazz.

LikeLike