Sixty Years And A Barrel Of Monkees

It is now 2026. A new year always sends my mind into reset mode as I realize how the things that happened 10 or 20 or even 40 years ago seem more recent to me than ever. Like this one – 2026 marks the 60th year since the multimedia phenomenon that was The Monkees. And, after some reading about and listening to the group in recent weeks, I have concluded that Davy Jones, Peter Tork, Mike Nesmith and Micky Dolenz deserve more respect than they have gotten over the years.

It was almost a decade ago that I wrote a bit about my history with the Monkees. Their 2nd album, “More Of The Monkees”, was the very first one that I bought with my own money as I was completing my 2nd grade of school in the spring of 1967. I went on to buy their next two albums, which I still have somewhere in my basement. I watched them on television every chance I got, and to this day remain disappointed that my school lunchbox was decorated with a generic cowboy instead of my four favorite musicians.

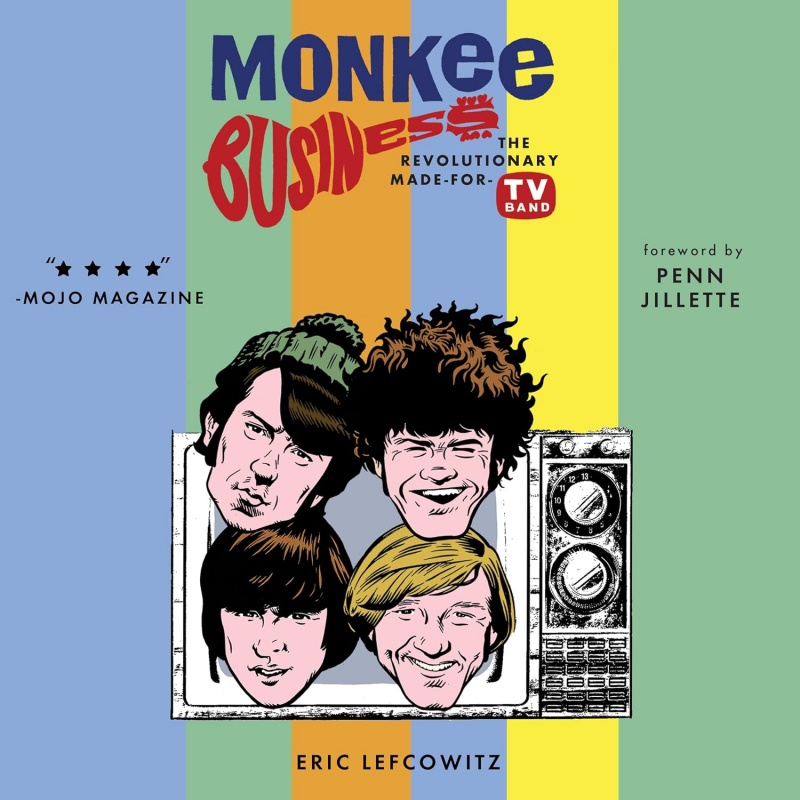

When I wrote about the Monkees in 2016, I had absorbed that societal prejudice against “the Prefab Four”, which considered them to have few talents and even less reason to exist, except to line the pockets of television producers. But I have changed my mind about them after listening to an audio version of “Monkee Business”, a 2024 book by Eric Lefkowitz.

The basic tale is fairly well known. In 1965, two up and coming guys in television got the idea for a weekly show about a rock and roll band. They were inspired by the success of the Beatles and their movie “A Hard Day’s Night”, and went about casting four guys who would play musicians in the show. And not just any musicians, but those willing to engage in spirited “Madness”.

Davy Jones (age 19) was the first in. He was already under contract with Screen Gems television, having made a small splash in a Broadway production of “Oliver”. Besides his acting and singing experience, Jones’ ace in the hole was that he was British, something that was musically huge in 1965. And it didn’t hurt that he had the look of a heartthrob.

The other young actor cast was Micky Dolenz (20). Dolenz was the child of acting parents and had been a child actor in a short-lived TV program of the 1950’s called “Circus Boy”, so he had an idea of how television production worked. He had also been the lead singer in a small-time cover band in his SoCal community who showed the beginnings of a winning personality.

The two cast from outside of the Hollywood-Broadway axis were actual musicians. There was Mike Nesmith (22), who broke through the mass of hopefuls by wearing a wool ski hat in the summertime. Nesmith was originally from Texas, raised by a single mother who rose above her secretarial career when she invented the product that became known as Liquid Paper. Interestingly, Nesmith is the only one of the four who actually came in response to the ad.

Peter Tork, the final choice (and the oldest, at age 23), was a friend of Stephen Stills. Stills had auditioned but was turned down because of his thinning hair and subpar teeth. Tork could play several instruments and went to high school in Connecticut before he moved to New York and played folk music in Greenwich Village coffee houses.

Tork eventually described the four-member group as “an arranged marriage”, and it is difficult to imagine four more disparate individuals brought together to form a group, with their only similarities being their age, their long-ish hair and their willingness to endure the grind of a weekly television show in exchange for making the big time in entertainment.

The television show was to be a comedy built around a struggling rock band, and was to include two song performances per 30 minute episode. From the start, the show was different from everything else on television. It incorporated slapstick comedy, frenetic action sequences, and a plot that usually involved either Davy being pursued by girls or the band trying to get hired for a gig.

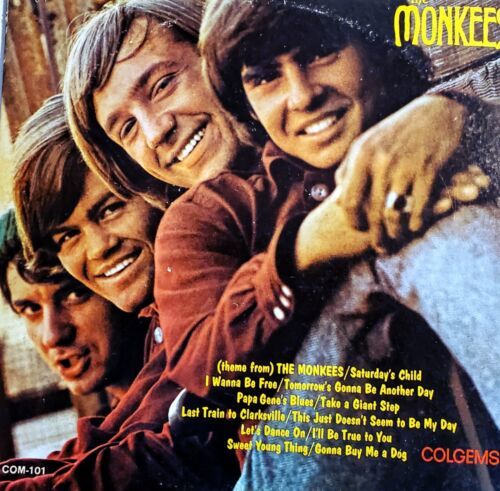

As the show’s debut was nearing, all of the music had been recorded by the duo of Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart. It was only near the last minute that the actual Monkees’ voices were dubbed over the instrumental tracks. The Boyce & Hart tune “Last Train To Clarksville” was zooming up the charts to a No. 1 hit status, and a debut album was in stores a month or two later.

This album and the second, “More of the Monkees”, were meant to feed the television show, and had almost no input from the actual Monkees, other than their voices. The New York music empresario Don Kirschner took control of the Monkees musical product early on, and supplemented Boyce & Hart with his contacts from New York’s Brill Building. Neil Diamond, Carole King and even Neil Sedaka wrote much of the band’s early output, though Nesmith contributed a handful of songs.

In addition to a grueling 5 day weekly shooting schedule for the show and evening sessions for recording vocal tracks, the young Monkees worked hard behind the scenes trying to become a real band. Dolenz reluctantly agreed to take the drums, noting later that he became one of a very small number of performers who sang lead from behind a drum kit. Jones never progressed beyond a tambourine or maracas. The band’s first live performance was in December of 1966 – and in Hawaii, presumably because it was as far away from the mainland press as it was possible to get. To the surprise of most, the band became known for putting on live shows that were quite good.

The band’s musical apex was probably the 1967 album, “Headquarters”. That album was the Monkees at their peak as a cohesive group, one where they had finally wrestled control over what they were going to play and how they were going to play it. Other than producer Chip Douglas (the bassist for the band The Turtles), it was the four Monkees who played and sang on every track. Though this album generated no radio hits, I am several listens in and will argue that it holds up quite well as a highly listenable slice of pop music from the tail end of “the mid 60’s”. The full album in its glorious original mono mix is available for listening here.

From late summer of 1966 through all of 1967, The Monkees were the hottest phenomena in both music and television. The show, described later as being far better than it had to be in its era, earned an Emmy at the end of its first season for Outstanding Comedy show. Even The Beatles were fans of The Monkees. And the music was everything that the institutional hitmaking colossus of the west coast could provide – catchy tunes, great session players and (to the surprise of many) Dolenz’ voice, which may be one of the best of his era and genre.

And then things went sour. It was inevitable that four young boys with widely divergent backgrounds and musical tastes could not permanently gel into a cohesive group. They were never best friends with each other, and after the “Headquarters” album, things turned into a collection of solo projects. Chip Douglas made it work on the group’s forth consecutive No. 1 album, “Pieces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd”, but the glue that held them together could not withstand the forces that were tearing them apart.

The television show was not renewed for a 3rd season. There was a movie project – eventually titled “Head” – that was an avant garde project that the fan base (and almost everyone else) rejected. Their fifth album, “The Birds, The Bees And The Monkees” was their first that failed to make the No. 1 rank (though it did peak at No. 5). A thoroughly disillusioned (and increasingly drug-dependent) Peter Tork was the first to quit in early 1969, and Mike Nesmith followed the next year, which sort of finished the whole Monkees-as-a-group thing.

But a funny thing happened. In the early 1980’s, reruns of The Monkees TV show started appearing on MTV and later on Nickelodeon, introducing the group to a new generation of fans. Dolenz, Tork and Jones then came together for a 20th Anniversary tour which resulted in a well received series of live shows that played to increasingly large audiences, as well as a new album collaboration by Dolenz and Tork. Jones, curiously, disapproved of the new album and refused to take part. And Nesmith, who had always been the most reluctant to do group projects, refused to take part at all.

The ensuing three decades saw periodic re-appearances of The Monkees as a touring show, in various combinations of Dolenz, Jones, Tork and eventually (and on fewer occasions) Nesmith. What all of them eventually learned was that The Monkees was an inescapable part of their lives, and that there was a deep well of goodwill from multiple generations of fans who had come to appreciate their offbeat show and what turned out to be an equally deep catalog of engaging music that was much more than just the radio hits. The band was good at multiple styles, which provided a lot of variety. The members’ differing musical “homes” – country (Nesmith), folk (Tork), Broadway (Jones) and straight-up rock & roll (Dolenz) – gave the group a musical range not often seen in their time.

I count it as a great tragedy that the original members did not perform together more often in their later years. That possibility ended when Jones died of a heart attack at the age of 66 in February of 2012. But even then, Dolenz and Tork (and occasionally Nesmith) continued their live shows and even did another album that was moderately successful. But then Tork died of cancer in February, 2019, leaving Dolenz and Nesmith to make what they billed as the Monkees’ Farewell Tour. After Nesmith’s death from heart failure in December of 2021, Micky Dolenz remains the last Monkee standing.

In retrospect, it is amazing that The Monkees accomplished what they did, given the group’s parentage of cynicism and commerce. But the four young guys who hit the pinnacle of success in their 20’s made enough deposits to the bank of fan goodwill that they were able to live off the proceeds for the rest of their lives. Someone (I forget who) once described The Monkees as a real life version of Pinnoccio. Only where Pinnoccio was a puppet who became a real boy, The Monkees were puppets that became a real band.

How good of a band? I will share one track that has captivated me lately. “The Girl I Knew Somewhere” was a Mike Nesmith composition that was issued on the B side of a single, with Mike’s vocal (listen here). This version was re-arranged with Micky singing lead during the Headquarters sessions. Inexplicably, this track was never originally released, but it shows the Monkees doing music all on their own. Note the great harpsichord solo of Tork, the wonderful voice of Dolenz and the fine song by Nesmith, and how it all comes together in an excellent pop song. Fortunately, re-issues of the “Headquarters” album did include the track, which allows us all to enjoy it.

I now make a full apology to Micky Dolenz and his now-deceased bandmates. Ten years ago I made some snide comments about a plastic band that had little in the way of talent, thinking that the best part of their records was the session musicians who I considered the makers of the music. After listening to both Lefkowitz’s book and to several hours of The Monkees’ music, I no longer believe that. Instead, I see four young guys who were thrown together under very difficult circumstances, and who eventually became the band they had been cast to portray. And in doing so, they brought us a lot more good music than they normally get credit for. So I am no longer ashamed to admit it, and will just come out and say it: I am a Monkees fan! And you should be too!

What’s really quite interesting is the idea of giving a band like the Monkees shit for being a manufactured entity, but completely giving a pass to everyone in the last 25 years (and maybe more) of pop.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really true. And even in the 1960’s, many, many pop groups did not do the instrumentals on their own records. The Beach Boys was just one other example, and nobody gave them a lot of blowback for Pet Sounds.

Something about The Monkees has retained old fans and made new ones while most of the acts you are probably thinking of have faded into obscurity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The acts I’m thinking of haven’t all faded yet… but most will be forgotten soon enough, replaced by other younger talentless ‘artists’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great essay. Your points and opinions are very accurate, I think. It’s hard to believe that only one Monkee remains with us. It seems like only yesterday . . .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Time certainly flies. And I suppose it is fitting that the one Monkee left standing is the one who probably did more to keep the guys together than any of the others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Weirdly enough, even back at the origin, I never looked at the Monkees with any kind of distain. I mean, we understood that they weren’t Cream or Buffalo Springfield, but that didn’t mean they were a target of our band snobbery. Passible pop hits and radio play (I mean, c’mon, I still love Boyce and Hart), and the fact that we weren’t quite sure that it just wasn’t a great goof that allowed four guys who could probably be our friends, to make a few bucks off “the man” while having fun. Who was using who? I have a pal that has pretty esoteric music tastes and it didn’t stop him from going to and thoroughly enjoying one of the 80’s and 90’s era reunion tours. The shows are run here on one of the nostalgia broadcast channels, and still somewhat hold up and aren’t “cringe-worthy”.

Lot of back stories for the boys, including Mike Nesmith being instrumental in the birth of music videos with his Pacific Arts company, and getting awarded the first video grammy for his experimental film “Elephant Parts”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nesmith was a fascinating guy. He was probably the most musically productive of the four, and wrote quite a few songs. He wrote Linda Ronstadt’s debut hit “Different Drum” – not everyone knows this. He was also ahead of the curve on the kind of countrified rock that took hold in the 1970’s, though his solo career came a little too soon to really cash in on it. He was also the guy who tried harder than the others to separate himself from The Monkees and to be known for something else.

I have listened to their first four albums several times now. The first two are great examples of the big hitmaking machine of the era. They are uneven, but the high points are really high. The second two (Headquarters and Pieces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.) are probably the best examples of their own musical tastes. I think both of them hold up quite well, overall. Headquarters was hampered by Micky’s struggles with the drums, but the group was really on the same page. The Pieces album brought session musicians back, so the backgrounds are better constructed, but the styles vary a little more and there wasn’t as much camaraderie.

The book I read points out that The Monkees live shows were almost always really good shows. One interesting story is that Nesmith (wearing a disguise) attended one of the Dolenz-Tork-Jones performances in probably the 90’s and felt like for the first time he really understood what the group was. He decided that they had been wrong sticking Micky with the drums because he was a natural front man, and was amazed at the amount of love he felt coming from that audience, and how the guys on stage soaked it in and sent it right back out there. It was after that experience that Nesmith started to become more involved again. That book is a great read/listen if you get the chance.

LikeLike

I believe that Jack Nicholson directed Head. The 1960s had several theatrical releases from TV shows. I’m thinking of A Man Called Flintstone and Batman as 2 other examples.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jack Nicholson was one of the writers, not the director. The director of Head was Bob Rafelson. Rafelson also directed Five Easy Pieces, The Postman Always Rings Twice, and the King of Marvin Gardens. He was also the executive producer of the Monkees TV show. Head is an interesting view. I have always found it to be quite surrealistic. Kind of like a “grown up” version of the Monkees tv show (where the drug of choice would be something other than Captain Crunch/Sugar Pops 😉 ).

Thanks for bringing up A Man Called Flintstone. I loved that movie and saw it well before I ever saw any of the James Bond films that it was a parody of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jeff. You know your movies!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have never seen Head. It doesn’t sound like the kind of thing I would normally like, but I think anyone who considers himself a Monkees fan needs to see it.

LikeLike

Jeff beat me to the Nicholson thing, but I will go on record as a huge fan of the Batman movie. I have never seen the other one you mention and will have to look for it.

LikeLike

Being too young to be around during their first run, and not having cable tv when they reappeared on MTV (which just shut down, incidentally) and Nickelodeon, The Monkees are a group I’ve been aware of, but that’s about it.

That said, years ago I discovered some hard bound book at my grandmother’s house. She was one to attend garage sales and then flip everything in another venue. Anyway, she had acquired a 1960s era book about The Monkees, which showed various exploits in still pictures. It was interesting to look at and gave some insight into a group I still don’t know much about.

From everything I can tell, it looks like while the arrangement was prefabricated, everyone benefitted, which isn’t a bad thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lots of things from my mid 60s childhood have not aged well, but The Monkees have aged surprisingly well in both the show and their records.

LikeLike

I’ll have to seek out that book, it sounds interesting. The Monkees absolutely got too much criticism from 60s hipsters but their music lives on in deluxe editions of albums, outtake collections, etc. Their career in the studio is better documented than many “real” bands from the era but that’s okay with me. It is really good stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I highly recommend the book! What will be interesting is to see if they make it into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame while Micky remains alive. The group’s decades-long snub from that organization seems to keep the snobbery alive.

LikeLike

I think the reason people were harder on the Monkees was because we didn’t know how much the music of the 60’s was not played by the actual bands. I certainly didn’t. I recently watched the documentary The Wrecking Crew which was about the session musicians and was totally shocked at how many records they played on and how little of the music was made by the bands whose names were on the record.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree – those anonymous musicians were more responsible for pop music in those days than we ever knew. I probably saw the same documentary, and have also listened to some interviews of Hal Blain and Carol Kaye. Fascinating stuff! It was such a departure from the way records had been made before.

LikeLike

Thanks for your research and comments about the Monkees! I always liked their show and their music. I watched a youTube about them last year and it echoed pretty much everything you said here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did not expect the depth of research and the depth of material about (and from) them. Their later successes were news to me. I should have paid more attention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I follow a blog by songwriter and musician Regie Hamm. His insights about the music industry make it fairly clear which artists achieve stardom and which ones don’t – and the price artists pay in trying to navigate the system. It is no wonder that the public is kept in the dark!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pop music and sausage have much in common. 😛

LikeLike

The more I learn about the Monkees, the more fascinated I become at their story. And whenever I want to test someone with some obscure trivia, I always refer to Michael Nesmith, for he was involved in a lot of different things, as you have pointed out. Who knows, if he had continued to pursue the video business, maybe MTV may not have degenerated into reality TV and shows totally unrelated to music at all!

Recently I saw video of the last performance that Dolenz and Nesmith did together, and I gained even more respect for them as they still put on a credible show and the fans truly loved them. It was apparent that Nesmith was fading, and shortly thereafter he passed away. Surprises me that that was back in 2021; time flies as we age.

Their screen tests are on Youtube. Nesmith’s is particularly interesting as he roams around, investigates the room, opening drawers, taking things out of cabinets, something I’m sure his interviewers had not seen before. It’s worth viewing for anyone who has an interest in the band.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would like to see those screen tests, they sound really interesting. As troubled as some of their relationships were, it was good to see them coming back together as they aged. And Nesmith was a fascinating guy.

LikeLike

For some reason your system won’t allow me to copy a link in here. Just google ‘Monkees screen tests’ and you’ll find several on youtube. enjoy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! The Monkees were a part of my Saturday morning routine. I loved them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I watched them in those Saturday morning reruns too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a great retrospective review.

I openly admit now to loving the Monkees, but early on, they were kind of a guilty pleasure. This came from a kind of unfortunate experience in what would have been the summer of 1967 when I went on a long family road trip to visit with my two older female cousins (who would have been around 11 and 13 at that point) and who were just ga-ga over the Monkees. I remember being ignored all weekend by these two as they devoted themselves to playing the records, watching the show (which obviously given that it was 1967, before videotape or anything that allowed repeat/on-demand viewing, only happened one time during the weekend), reading various fan magazines and otherwise completely ignoring me and my (younger) sister. This “rudeness” (according to my mom, who admittedly had a very hard time with “teenagers”) all elicited a very very negative reaction from my mom…which she used against my poor cousins for the rest of her (my mom’s) life. And let’s just say that “those damn Monkees” became somekind of avatar for rude relatives in my family.

Mom grudges are the worst grudges…

My cousins, btw, are just fine now…and we still laugh about my lost Monkees weekend at the age of 6.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jeff, and what a great story!! I was too young for fan magazines back then but might have been just fine hanging on the sidelines if they had read aloud. 😁

For those who weren’t around then, it would be hard to understand what a cultural force they were in 1967.

LikeLike

JP, I enjoyed reading this post and learning more about the Monkees. When we moved to the States in the Summer of 1966 I had not heard of them as I didn’t own a radio until I got a transistor radio, a few years later, but when I started school in the Fall, they were very popular, so popular that one of our crafts was a linoleum block where we carved the Monkees guitar logo into it. I haven’t a clue what we used them for. I remember watching the show, one of the few TV indulgences I had during the school year on a school night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Linda! I would have loved it if my elementary school art or music classes would have incorporated some Monkees into their lessons, but it never happened for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, that was sixth grade JP and probably we would have been better off education-wise with a more intelligent activity. My City’s school system was not the best – hopefully it has improved since I graduated from high school in 1973.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a fun look back! I remember all of the album covers, as I was a huge Monkees fan, both of the music and the TV show. The Beatles passed me by, but at ten, I was old enough to appreciate rock music by then. Mickey Dolenz and David Jones were my favorites. I had their pictures from Tiger Beat magazine taped to my bedroom wall. Sadly, my fandom did not last, as when they came to tour my small hometown in 2002 I did not go see them, although 5000 other people did. I was working that night, and only heard about it the day before, but it was too much of a hassle to change my shift, although there would not have been a problem getting tickets as the outdoor venue was a racetrack in mid-July. There were only two of them there, but when I googled it did not say which two, but I think Mickey Dolenz was one. If someone had told my ten year old self that I could go see the Monkees in person in my small home town I would have been deliriously happy! Some of their hits have held up quite well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Joni! Was there a single 10-13 year old girl in North America who wasn’t gaga over Davy Jones? As a boy, he was my least favorite. I think Micky and Mike were my faves, with Peter close behind. They could have thrown Davy overboard to join the other Davy Jones and I would not have cared when I was 8 ot 9 years old. 🤣

I’m sorry now that I never saw them in their later years. Everything I have read says that they always put on an uncommonly good show.

LikeLike

HA re Davy Jones! I think he was probably every girls favorite – the British accent. Looking back, he was cute, but I wonder what the heck I saw in Mickey, as he just looks kind of goofy? They did put on a good reunion show here, from what I heard later I wished I had gone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Micky had the biggest personality of all of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t remember…..but that might be why?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! Great “name check” for Tiger Beat! A seminal “fan-zine”. My older sister cut her favorite pictures out of it and put them in a scrap book! Reading the Wiki entry for Tiger Beat led me to find out the same people did a magazine called : Monkee Spectacular!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiger_Beat

LikeLiked by 2 people

HA! I remember a typical article being, Davy Jones idea of a perfect date!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m surprised to read there were only two seasons of the television show. Then again, those episodes came along in my formative years. A few of their hits are playing in my brain now, as fresh as if I’d just downloaded them on Spotify. I wasn’t aware of their success beyond the show and into their later years (other than Davy Jones’ guest appearance on “The Brady Bunch”), so that made for an interesting read. Finally, any insight on the name “Monkees”? I always assumed it to be the plural of “monkey” but it looks more like a play on the word.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read that they tested a handful of names but that Monkees scored best by a lot.

As an adult, I met a lady who won a date with Davy Jones through a fan magazine contest when she was a young teen. She remembered that he was nice, but that he didn’t seem unhappy when it was over.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Celebrating the 60th, Rhino Records has issued all of their singles (both sides) as a 2 CD set. Fully remastered! The CDs I used to own were not remastered, and it was evident. https://store.rhino.com/products/the-as-the-bs-the-monkees-2cd

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Rhino did some album re-releases several years ago, too. This sounds like an interesting set.

LikeLike

If you want to believe the Googles AI (and believe me, I find mistakes in it all the time), they say that in 1967 America, the Monkees sold more albums than the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined! I’d like to see the stats, but if it’s true, that’s amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That might be true – they had their first 4 albums in stores that year and all were selling briskly.

LikeLike

Wow what a story. 🤣😎🙃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Yes, it is a story unlike any other I have read about the music business.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just thought of another Monkee-related tidbit. There’s a Spongebob Squarepants episode where Davy Jones appears as himself in a reference to ‘Davy Jones locker’. He throws smelly socks at a ghost of the Flying Dutchman, who’s in his locker, while singing Daydream Believer. Of course kids (mine included) had no clue of the connection, but for parents watching the show with their kids, it provided some levity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, that’s funny!

LikeLike

Yesterday I was listening to the Sirius XM channel “80s on 8” and DJ (and original MTV VJ) Mark Goodman listed various permutations of “Valerie” as one of the most popular song titles (referencing Steve Winwood’s 1982 “Valerie”). The one version he omitted? The Monkees’ “Valleri”. Bad! Bad DJ!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: JP’s Book Report – Winter 2026 Edition | J. P.'s Blog

I love listening to music but my tastes are primitive. I grew up on Rock ‘n Roll with my friends (some were in bands) but when I was alone in the car, I listened to Country Western. I hated going to the Opera. Two of my sons were musicians. I thought the oldest sounded terrific when I was able to recognize he was playing Barbara Ann on the sax in his room. My youngest son sang in an elite choir in college. Once when he was singing in a group in Middle School, I whispered to my wife that they sounded pretty good. She whispered back, “They are absolutely awful!” I would be enjoying him practicing on the piano at home and from the other room, I would suddenly hear my wife shout from the other room, “Slow down. You are ruining that song!” I liked the Monkees but knew better than to say anything good about them around sophisticated music lovers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think hindsight has proven that the rock snobs who hated The Monkees were wrong. For what they were at the beginning, the group went farther than they had any right to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What, no mention of the Monkeemobile? 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I looked that up later, it seems there are a couple of them still floating around out there. I ought to find time to do something about it for CC

LikeLike