McKinney’s Cotton Pickers – The Detroit Band That Schooled The World

Ever since writing last month about the electrification of the process for making phonograph records in the 1920’s, I have been in a 20’s jazz state of mind. Make no mistake, there was plenty of bad music put on records in “the roaring 20’s”, and you can thank me for sampling through an awful lot of dreck so that you don’t have to. But the decade was not called “the jazz age” for no reason, and with some noodling around you can find some mighty good music from the era. And there is no doubt that a Detroit-based band known as McKinney’s Cotton Pickers produced more than their share of it, and influenced the world of jazz more than most people are aware.

It is virtually impossible to write about jazz of the 1920’s without touching on race. That decade was probably the peak era for racial segregation in the music business, when there were black bands and there were white bands, and there was close to a zero chance that any racially mixed group would get into a recording studio. Those lines started to crack in the 30’s and were mostly obliterated by the end of WWII, but in the 20’s they were a bright line.

The stereotype was that the popular white bands played cleanly and with precision, but were quite tame. The black bands were more free-wheeling, though at the price of being a little raggedy and not very good with reading music. But what if you could combine the best parts of both stereotypes? You might end up with this band – one that could play tight, complicated written arrangements without giving up any of their jazz cred. In fact, there may have been no band that did it as consistently and as well as McKinney’s Cotton Pickers.

William McKinney was a drummer and showman who formed a band in Springfield Ohio in 1922, and moved on to Detroit where he either re-formed or re-named the band as the Syncho Septet in 1926. He assembled a core of top players, including drummer Cuba Austin, trumpeter/arranger John Nesbitt and reed player Prince Robinson and the band was becoming something to pay attention to. In fact, once Austin came aboard, McKinney stepped back from his drums and worked at getting bookings.

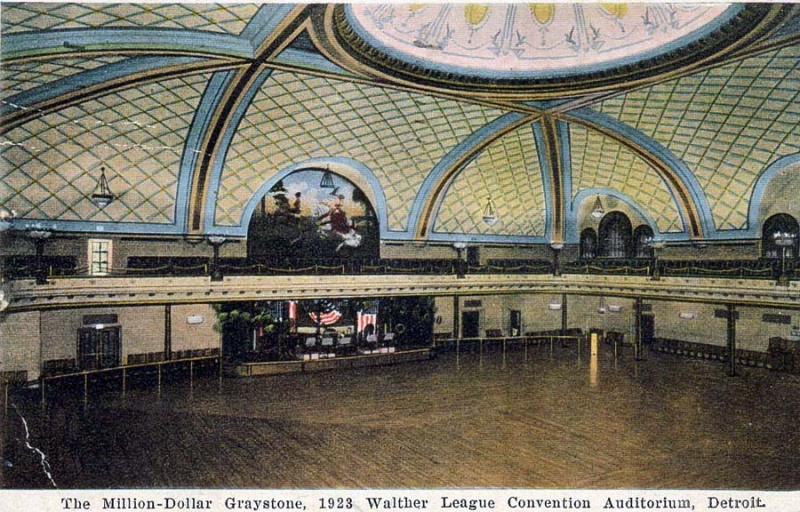

Musician/manager Jean Goldkette was a big figure in the era, who boasted a white band that was one of the best jazz outfits in the business before its towering payrolls forced him to disband by 1928. As co-owner of National Amusement Corporation, Goldkette took over management of McKinney’s band with an eye to getting this hot new outfit into the mainstream, with a steady gig at Detroit’s massive Graystone Ballroom and into a big-time recording studios of Victor Records. One of his first acts was to hire a saxophone player/arranger named Don Redman away from the Fletcher Henderson band – a New York band that owed as much to Redman as to anyone for its success in the 1920’s. Goldkette’s other act was to re-name the band as McKinney’s Cotton Pickers.

That name, so unfortunate for we moderns, was not all that popular with the group at the time either. But Goldkette wanted a name that would evoke the south (even though this wasn’t a southern band) as a way to hitch onto the New Orleans mystique that was such a big part of authentic jazz in those days. When told that the new name was a take-it-or-leave-it part of a package deal, the band reluctantly accepted.

The good part was that MCP became probably the first black band to break out of the “race records” category and into the mainstream with a Victor recording contract. It was under the creative energy of both Don Redman and John Nesbitt that the band became one of the top bands of its day, regardless of racial makeup. Jazz writer Gunther Schuller argues that the Cotton Pickers was one of very few really good bands of the time, and in some ways was surpassed by none in the way they consistently maintained their high level of musicianship. (1)

In fact, this band put out so many excellent records that it was quite the job to pare things down to a manageable 3 selections. It took a lot of time but your intrepid editor got the job done, so here they are.

The MCP’s first recording session was June 11, 1928 for Victor Records in Chicago. One of the products of that session was “Crying and Sighing”, an arrangement written and arranged by trumpet man John Nesbitt. This band sounds far larger than its 11 players, and points the way to the kinds of arrangements that were written during the big band era of the following decade, with taut section work broken up by excellent solos.

Redman himself takes a solo on an unusual instrument called the celesta, which was a sort of mash-up of a keyboard and a vibraphone. Also notable is the trumpet work of Nesbitt, who proves himself here as every bit the equal of the great Bix Beiderbecke in his ability to sound far more modern than his era. Prince Robinson is heard on both the brief clarinet solo and also the tenor sax bit at the end, which was backed by the rest of the band. Drummer Cuba Austin should be better remembered than he is, because he could really drive this group with a light touch on the cymbals. (2)

The second selection comes from the band’s 5th recording session, in Camden, NJ on April 5, 1929. “Will You, Won’t You Be My Baby” is notable for its style, which sounds far more modern than its recording date would suggest. This is another Nesbitt arrangement (3), notable for its early adoption of a swing rhythm taken at a far more relaxed tempo than was the norm. That swing beat smooths out the bouncy rhythm of the day by going from an even 1-2 beat (DAH-dah DAH-dah DAH-dah DAH-dah) to more of a flow (Daaah-da Daaah-da Daaah-da Daah-da) that stretches out the 1st and 3rd beats of a 4 bar measure, and which became the foundation of almost all jazz (and pop music) until the advent of rock and roll. Really, this sounds like something that could have come from a good band in the mid 30’s and still have sounded modern.

John Nesbitt and Prince Robinson trade trumpet and saxophone solos with another modern touch – the full band providing background as they do so. Really, the piano solo may be the only place where the performance seems no better than average.

It’s impossible to write about MCPs and not mention the series of records made under that name in 1929-30. The band was so popular at the Graystone that it became a problem when Victor Records asked for them to record at its New York studio. The solution was for Redman to take a skeleton crew of himself, banjo man Dave Wilborn and his trombonist Claude Jones to New York and then and fill in with locals for the sessions. But not just any locals.

The popularity and influence of this Detroit band is demonstrated by the caliber of musicians who happily subbed in to play as Cotton Pickers. These records featured a veritable Who’s Who of Harlem’s top young jazz players, mostly regulars from the bands of Fletcher Henderson and Benny Carter, who took part in a 3-day session of November 5-7 of 1929.

Our third selection, “The Way I Feel Today”, is from one of these sessions, and included young up-and-comers like Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins and Fats Waller as the best-known of the ringers.

This is a Redman arrangement that swings as hard as anything from 1929 possibly can, and features MCP trombonist, Claude Jones. The rhythm section works really well here, with MCP regular Dave Wilborn’s banjo, Fletcher Henderson’s drummer Kaiser Marshall and the tuba of Billy Taylor. Another surprise comes after Joe Smith’s trumpet solo, when Don Redman’s half-spoken vocal is backed by the sparkling keyboard that was unmistakably the great Fats Waller. The record finishes out with a solo by a 24-year-old Coleman Hawkins, then beginning a long and distinguished career as one of the great tenor saxophone men of jazz.

In the 1960’s, the records for many top bands were made by a bunch of professional session musicians in Los Angeles (commonly called “The Wrecking Crew”), who were far better players than the actual members of the bands. These MCP records from New York were not like that – these performances are not better than those made by the actual Cotton Pickers, just different. The Detroit players may not have been the big names, but they were far more influential than they probably understood at the time. No less a light than Duke Ellington once remembered the Cotton Pickers, stating “That bunch… made a gang of musical history, and their recordings had everybody talking about them.” (4)

So, if this band was so great, how come it isn’t better known today? The Depression was hard on the band, especially given its small local market. It appears that the band lost its connection to Goldkette and the Graystone, and settled into a grueling tour of short engagements in the middle of the country in 1930-31. Redman left shortly after that tour to form his own band in New York, and the MCPs fell back to the uneven management of McKinney before disbanding in either 1933 or 1934, though it was revived a couple of times in various forms.

I guess the band’s arc was more or less like that of the 1920’s in general. There was some special magic that lasted for a time, and then went away. As great as the band was, it remained a Detroit band and probably suffered more than the bands that could count on the larger audiences of New York. Redmond remained active in music for many years, eventually becoming musical director for Pearl Baily in the 1950’s. John Nesbitt, on the other hand, is much more obscure and seems to have died from alcoholism in the mid 1930’s. Banjo player Dave Wilborn stayed in Detroit and led bands for several years. He was believed to be the last surviving member when he joined a Cotton Pickers revival band in the early 1970’s.

As for its being forgotten in the modern day, I have no doubt that the of-its-time name has not helped the band’s cause. And nor has the tendency of musical snobs to boost the players from the New Orleans tradition over groups that they would derisively lump into the “dance band” category, especially one popular in its day with mainstream audiences. But despite these headwinds, there was probably no other “territory band” of its era that exerted the kind of influence normally reserved for the big eastern jazz outfits of Ellington and Henderson. Fortunately, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers left a small but valuable treasure in its catalog of Victor recordings. These old records can remind us of how McKinney’s Cotton Pickers did what all good jazz should do – bring everyone together for a great time.

- Most sources credit only Redman, a prodigy who had a college degree in music, for the band’s high musical quality. Schuller, however, argues that Nesbitt, a self-taught trumpeter, was at least as responsible for the band’s trajectory, if not moreso. “The Swing Era – The Development of Jazz 1930-1945” by Gunther Schuller, p. 301 (as found on Google Books).

- Discography/personnel information is taken from “The Recordings of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers” by Charlie Irvis.

- Most sources assume that this was a Redman arrangement, but Schuller makes a strong case for Nesbitt.

- https://musictales.club/article/great-depression-cut-short-extraordinary-dance-life-mckinney%E2%80%99s-cotton-pickers

Excellent entry today. Honestly, a “deep dive” for me. Heard the name a few times but never the music. I’m a “plus one” for the name being a “problem”. There were a lot of jazz labels scouring the basement vaults for reissue material in the late 60’s to early 80’s, and I can imagine people running across archived material and thinking “…why bother opening this can of worms…”. Tough luck for us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

BTW, a quick dive on the webs, and plenty of reissued CD’s today! I’ll have to buy one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are also a number of records available for free on YouTube, including one full album that is pretty good. And I am with you – the name of the band didn’t do any favors for the jazz tastemakers of the 1950’s and later who were delving back into doing reissues of the old stuff. Really, I think the only reason Fletcher Henderson remained as well known as he was resulted from Benny Goodman hiring him around 1934 after his band went bust. So many liner notes of album reissues gave credit to Henderson for BG’s early arrangements.

LikeLike

Thanks! I joked with family that this one must be what it feels like to give birth. 🙂

I was amazed at how little information there is beyond stuff at the very surface. I still don’t know what happened to get the band separated from the Goldkette/Graystone/Victor trifecta that had sustained it early on. Maybe it was just the Depression, but I sure couldn’t find it. Also interesting is that some of the players, like tenor sax guy Prince Robinson had been a genuine big deal early on, and late in life Coleman Hawkins remembered how Robinson had influenced him. I loved his playing on the first two records I featured, but he bounced around several groups through the 40s and never really broke into the first tier despite his skills. And Don Redman’s band seemed to be a really popular early swing outfit, even featured on one of the Fleisher cartoons (Betty Boop, in this case). But despite being active in the business for decades, he stayed under the radar after the 30’s. At some point I need to take a dive into Fletcher Henderson – from what I gather, his band had more star soloists, but was more uneven in the quality of their material.

LikeLike

Speaking of Goldkette, am I the only person that wonders why there’s always a lot of band pictures of him where he always seems to be holding a pistol? Running a band must have been a tough business!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, I have never noticed that!

LikeLike

Well JP, I should be “crying and sighing” since I have lived in the Detroit area now since 1966 and never heard of this band … I am sure the jazz enthusiasts that flock to Detroit’s annual Jazz Festival at Hart Plaza are aware of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Linda, as a jazz aficionado, as well as a subscriber to Down Beat Magazine, I’ve learned that the Detroit Jazz Festival is quite the event, and a major sponsor is the grand-daughter of the Carhartt work clothes company, also a big fan and booster of Detroit! Wonderful to have someone like that involved in the city and events!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve never been to the Detroit Jazz Festival Andy, but I know it is touted as being the largest free jazz festival in the world. It seems to me like they stream portions of the Festival as well. I didn’t know that about the Carhartt granddaughter. Carhartt is big in Detroit, so yes that is good! The City of Detroit is making a comeback and yesterday on the news they said the population had grown for the second year in a row. This is likely due to many people coming to Detroit last year for the NFL draft and seeing how revitalized the City has become.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was surprised at how obscure this band has become. I was wondering if you had ever heard of Detroit’s Graystone Hotel. I think it got torn down in the 1970s or 1980s, but it was apparently a wonder in its day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, I’ve not heard of Detroit’s Graystone Hotel JP. Did they eventually tear it down as a result of the ’67 riots? A lot of the buildings that sustained damage during the riots stood empty for years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wasn’t familiar with it either. This article Backstage at the Graystone | University of Michigan Heritage Project suggests that it was designed as a larger hotel, scaled down and possibly never really completed? The last owner seems to have been Berry Gordy the Motown founder, who basically abandoned it when they moved to the West Coast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure what happened there, I meant to change the link to this article which has more details. Backstage at the Graystone | University of Michigan Heritage Project

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what a great story about the Graystone! Thanks for the link!

LikeLike

Good stuff. We should be remembering these older groups more often. 🤣😎🙃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! And I agree completely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Couldn’t help toe-tapping on “The Way I Feel Today”. My brothers and I took a trip to Detroit last fall to see the Ford factory. We couldn’t get into the Mo-town museum (reservations recommended!) but we did make it to the Detroit History Museum, which is well worth a look around considering all Detroit has been through over the decades. I expect MCP was featured in this museum; I just didn’t appreciate their work until this post. Really interesting read/listen, J P – thanks. Also, I was struck by the celesta (which I’d never heard of before, even though I’ve played the vibraphone), and the use of the banjo in a jazz ensemble. Anything with a banjo works for me (except, regrettably, watching “Deliverance” 🙂 )

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m with you on the banjo – banjos and tubas had been common before electric recording, when their strong sounds were necessary. But they were soon replaced by string bass and guitar. And ditto on the celesta!

Thanks for the encouragement. Sometimes I fear that going too old with the music loses a bunch of people. Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person