The Microphone Century – The Electric Revolution In Sound Recording

I am having a lot of trouble thinking of things that happened in the 1920s as being a century ago. A comment to last week’s blog got me to thinking about this. In my aging brain, things like the Old West, steam locomotives and U.S. Presidents with beards and high, starched collars were the kinds of things from a hundred years ago. But this is no longer true, because we are now a full century removed from the year 1925. In mulling over this sorry state of affairs, I came across another thing that has hit the century mark – the electrical sound recording.

In its day, electrical recording of voices and music was a huge deal. And it still is.

Before 1925, the commercial recording industry was wedded to a process that was purely mechanical and acoustic. Musicians would play into a big horn, which would then transmit the sound vibrations through a stylus and into a wax cylinder or disc, which was then reproduced for sale. And of course, the customer played it back by doing the opposite – a stylus would “read” the grooves in the record and those vibrations would be amplified through another horn for listening. Although there were small improvements along the way, for the most part the system that Edison used when he invented the phonograph in 1877 was still in use nearly 50 years later for anyone who wanted to play music at home. [We have covered some of this development previously here and here]

Here is a short demonstration of the sound quality from that equipment, an acoustically recorded disc played on a vintage Victrola. Not a single electron was harmed in the making or reproduction of that music, with the player even using a wind-up crank instead of an electric motor for the turntable.

You will notice how flat it all sounds, with loud, sharp instruments like trumpets coming through pretty well, as well as the bass being provided by a tuba. You should also know that Victor was the 800 pound gorilla of the recording industry of the day, so a Victor record on a Victor player was probably about as good as you were likely to get. But technology was moving quickly in the mid 1920’s.

The period of about 1919-1923 saw several stabs at recording sound through an electrical microphone. These experiments, on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, resulted in varying (but low) degrees of success. It was Western Electric (yes, the company that probably made your grandparents’ telephone) that was the first to assemble a commercially ready system. That system, which it called the Westrex Process, combined a microphone with some amplifiers that would mate to the existing mechanical cutting systems for making records. The result was a system that could pick up far more frequencies, and which could also adjust those frequencies, filtering some and boosting others.

It is said that if you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door. But Western Electric had a little more trouble than that. Columbia and Victor were the two big record companies in early 1925, and neither was interested. Victor was against paying license fees for anything “not invented here” and was further wary of tech that might give a boost to radio, something it viewed as a threat to its existence. Columbia was interested, but was a financial mess and could not afford the license fees.

The British affiliate of Columbia was interested, but Western Electric insisted on selling to a U.S. company. I guess not as much has changed in a century as we might have thought. English Columbia resolved this problem by buying American Columbia and using the Western Electric system on both sides of the Atlantic. After which, Victor changed its mind about the idea and bought its own license.

So, what was the first electrical recording? This is a little murky, but it is believed that Columbia was first to fire up the mic on February 25, 1925 for Art Gillham and his Southland Synchopaters, who performed “You May Be Lonesome”. You will immediately notice the giant improvement in the sound quality. This recording has surely benefitted from some modern clean-up and top-quality play equipment, but these advantages require that the sound be captured in the first place, which it absolutely was here. And it is notable that Columbia chose to record the man known as “the whispering pianist” and his soft voice that was so unlike the full-chest vaudeville-style singer that had done so well on records of the recent past.

Victor was at it the following day, February 26th, with what it billed as “A MIniature Concert” on two sides of a large 12-inch disc. Instead of choosing performers better suited to the new technology, Victor rounded up some of its older-style best sellers, including Billy Murray. Murray had been singing on records almost as long as records had been around, and had to work a bit to adapt to the microphone. And you will be forgiven if you don’t make it all the way though this 1925 version of easy listening or adult (not-quite) contemporary.

But in a curious turn of events, these two records (which some have called experimental) were not the first ones released to stores. What is believed to be the very first commercial release of an electrical recording was a bit of an oddity by The University of Pennsylvania’s Mask & Wig Club. This disc was recorded March 16, 1925 and released April 9, 1925 on Victor Records’ Camden label. The club was a popular act in those days, and being right across the Delaware River from Victor Records’ Camden, N.J. headquarters, made it convenient for Victor’s house orchestra led by Nat Shilkret to provide the band behind the vocals.

This record, a medley of songs from the Club’s original production of “Joan of Arkansas”, is in a much more modern (for 1925, anyway) style. It would be a few years before the upright string bass would replace the tuba, but this record is at least a little more representative of the period we call “the jazz age”. But I will admit that even this one is a stretch for modern ears.

One source argues that the electrical recording that may have had the most impact as a showcase for the Westrex Process’ capabilities was a disc recorded March 31, 1925 by the Associated Glee Clubs of America, with “John Peel” and “Adeste Fideles” on the two sides. This was notable because the microphone could capture 850 voices in New York’s Old Metropolitan Opera House. This is something we take for granted now, but recall that before this new technology, recording vocal groups was limited to just a handful of voices in a small room. This video of a really pristine copy of Adeste Fideles demonstrates some amazingly good sound from a 1925 recording.

Another thing that has not changed in the last century is the way big business deals with tech. You might think that Columbia and Victor started clobbering each other with new electrical recordings – but you would be incorrect. It seems that both companies had large stocks of un-released acoustic records which they (rightly) assumed would become unsellable once electrically-recorded records became widely available. They dealt with this by reaching an agreement to withhold any publicity about the new process until November of 1925, giving them a bit over six months to push the old stuff onto the buying public.

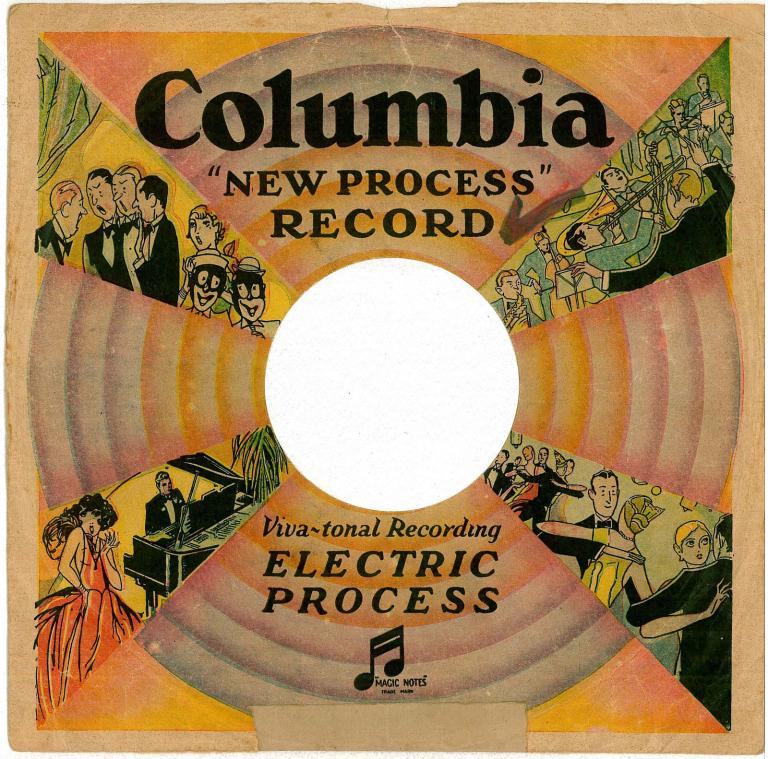

But after November, both companies pushed the new records (Viva-Tone at Columbia and Orthophonic at Victor). I would suspect that the second purpose in the publicity delay was to allow both companies to quickly developed new phonographs. Which they did, with machines designed to take full advantage of the fidelity available on the new discs by playing the sound through an electric loudspeaker and on an electrically-powered turntable. By 1927, pretty much the entire recording industry had either switched to an electrical system or gone out of business.

These records and their new phonographs would pretty much remain the state of the recording art in the U.S. for the next 20 years, until the long-play record revolutionized the playback side and magnetic tape provided the next tech jump on the recording side.

And the biggest impact was the new kinds of music that this tech could preserve for us to listen to a hundred hears hence, and the way that the music of The Jazz Age really comes alive in the second half of the 1920’s. I cannot leave a topic like this without giving readers something decent to listen to, so let’s take this example: Eddie Lang on the guitar and Joe Venuti on his violin playing “Black and Blue Bottom” in 1926. These delicate and nuanced performances on string instruments would never have come across anywhere near intact before the advent of the electrical process. Here is an instance of recording technology and great music coming together for us to enjoy as long as the technology remains to play it.

If you missed my feature on Eddie Lang and Joe Venuti from a few years ago, click HERE

For anyone who wants to really geek out over this topic, a British company has assembled a collection of early electric recordings at pristineclassical.com, which includes some very detailed producer’s notes, some of which were helpful in writing this short summary. https://www.thedp.com/article/2025/04/penn-mask-and-wig-100-anniversary-electrical-recording

Great entry, and it reminds me of a book I purchased, called: Song Catchers, by the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart. One of the things I learned reading it, is how big a collection of world sounds the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv has in its collection, started in 1900. The other thing I learned, is that well into the 1930’s researchers were still using Edison Cylinder recording machines, to capture native songs and language, in the far corners of the world; mostly because portable unit’s could be folded in a small case, with room for the cone, and it needed zero power, because you would wind them up.

LikeLike

This is a great point – sometimes even really obsolete tech remains perfect for an uncommon task or niche. I’ll bet that sound library would be fascinating! As well as how they protected it through two world wars.

LikeLike

The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv story, including what happened during the wars can be wiki’d, but an interesting fact is that the last Edison Cylinder recording in the archive was made in 1953 (!), and this was two years after the introduction of the portable Nagra reel-to-reel recorder!

LikeLike

Wow, I’m amazed that cylinders were used for that long!

LikeLike

Terrific article!

LikeLike

Thank you, sir.

LikeLike

I love it when you do these historical bits. I can’t wrap my head around 1925 being a hundred years ago, either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Obsolete tech is something I find irresistible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Having lived in both centuries, it is hard to believe 1925 was 100 years ago. The city I live in will celebrate its 100th year of existence this Summer and the local newspaper and the City’s social media page has been touting this big anniversary with many vintage photos of the main street and businesses back then with the old cars all in sepia-toned prints.

LikeLike

Linda, along this line, I was having a conversation with a young lad at the coffee shop about music, and I was recommending a group that had a few albums out in the 90’s that sounded like the stuff he was listening to. He looked them up on his iPhone, and said in a rather disdaining voice: “…this record is from 1992…”! I realized he hadn’t even been born yet, but I told him: “…that’s yesterday to me!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andy, I’m guessing you, like me, were not in the camp of “don’t trust anyone over 30!” When my elderly eye doctor retired suddenly back in 2005, I requested my chart as I’d seen him for decades. My new eye doctor, introduced himself and said with a sneer “it says on your chart you began wearing contact lenses in 1974; I wasn’t even born yet!” Well, nothing like meeting a new patient and making them feel like they’re over the hill!

LikeLike

Boy, I’ll tell you Linda, there’s a real disconnect between the modern generation and knowledge that they should really be interested in learning. I was horrified a number of years ago, to find that millennials didn’t want anything to do with being mentored by older people and learning the common knowledge. They hated older people. I was in advertising photography and we revered the people in our industry in their 60’s and 70’s, when I was in my 20’s. We sat at their feet like we were learning from Plato. Modern millennials don’t want to know, and are trying to reinvent the wheel, every time they do something, to avoid having to acknowledge their “betters” and more educated.

LikeLike

Just think how mind-blowing it will be in ten more years and 1935 will be a century ago. When your parents were born 100 or more years ago, that’s something to think about. Marianne’s father would have been 100 this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, time is so fleeting, really it is. My parents both were born in 1926 so would have turned 100 next year. Heck, I’ll be 70 next year and that seems inconceivable to me!

LikeLike

That was a fun post to listen to!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think those first few recordings are going onto peoples’ playlists, but I think there are few better time capsules than old records.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for another stroll down memory lane! We still have a record player and an assortment of records. Some of them belong to a parental unit who wanted us to digitize the record so she could listen to it on her i-something!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, an update on the old “I’ve already paid for the music so let’s transfer the records onto CDs” thing. I did that with precisely one record. I bought a digital converter and uploaded both sides of an LP to my computer. By the time I broke out and named each track and uploaded cover art to associate with it, I decided that the $12.99 (or whatever new CDs of re-issued albums cost then) that I could upload into my computer for iTunes was a bargain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(Catching up on all things J P.) The progression of the quality of the output as you move through the recordings you posted is evident. Didn’t know the tuba ever served as the “bass”. As I watched the video of the “Adeste Fideles” recording I couldn’t help noticing how quickly the stylus moved across the record. A minute into the performance and the stylus was already halfway across. Gives me a new appreciation for “LP”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there was a big difference between the 33 1/3 rpms we grew up on and these old 78 rpm records. About 5 minutes of music on one side of a 12 inch disc, 3 minutes on a 10 inch. I find it so interesting that pop songs have mostly stuck to that 3 minute benchmark even though there has not been a technical reason for it for over 80 years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Happy 100th Birthday to Sweet Georgia Brown | J. P.'s Blog