Magnetic Tape In The Recording Industry – This Changed Everything

Your faithful scribe has periodically gone into a geekfest over obsolete methods of reproducing sound. Up to now, we have gone into a variety of old sound media, including Edison cylinders, 78 rpm discs, and newer long play formats. We have paid less attention to the backroom processes – how the music was captured in the first place. That will be today’s topic – how magnetic tape replaced hot wax in recording studios everywhere. It was this process (more than any change in playback media) that changed everything.

Many of us have all heard the term “wax” used in connection with phonograph records, or at least heard it as late as the 1970s. There was some truth there because from pretty much the beginning, most recording processes began with the use of wax. Early Edison cylinders were made from wax, and were recorded directly from a performance to be sold for playback on the pricey machine in someone’s parlor. Later, wax was used for initially capturing the sound. Molds were made from those wax masters as a way to press a large number of copies.

This process was demonstrated in a short film made in the 1940’s, showing how the process worked at RCA Victor. That film (above) shows the process of creating the wax master starting at about the 1:30 mark and continues to about 5:15 (with much of that time showing the orchestra playing the Blue Danube Waltz). In short, the process involved making a disc that would be identical in dimensions, speed and playing time with the mass-produced discs that would make their way to record stores.

Although these acoustic wax discs took over the commercial recording industry and dominated it for fifty years, there were other methods of recording sounds. As early as 1898, a Danish engineer named Valdimar Poulsen discovered that sound could be recorded using magnetized steel wire. That wire could be magnetized by a recording head as a way to capture sound, which was played back over a non-magnetized head. The wire passed the head at high speed, with the standard eventually becoming 24 inches of wire per second, so that a one-hour recording required a 7,200 foot length of wire.

Before 1930, German sound engineers developed the ability to do the same thing with magnetic tape in place of steel wire. Using a paper tape with a layer of iron oxide affixed by laquer, German companies (including IG Farben) were developing sophisticated equipment around tape technology. Nazi Germany was not known for sharing its technology, and the development of tape recording was done with great secrecy. It was not until the end of the war that Allied engineers could learn how highly developed the German systems had become.

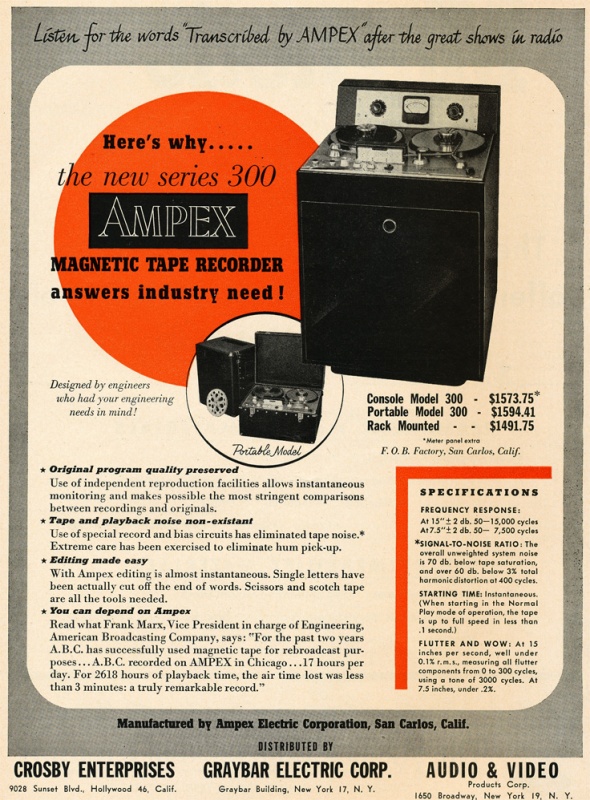

Back in the U.S., a Russian-American inventor named Alexander Matthew Poniatoff formed Ampex Corporation in what would become California’s Silicon Valley. At the end of the war, Ampex obtained a pair of German “Magnetaphon” machines, along with quite a few reels of BASF tape. Unhampered by patents (German patents had been effectively voided after the war), Ampex became the leader in further development of magnetic tape recording.

By June of 1947, Ampex demonstrated one of its new machines to the popular singer Bing Crosby, who detested having to record his weekly radio shows live. The test of the machine (which was now using a ferric oxide-coated acetate tape developed by 3M) was successful and Crosby became a major financial backer of Ampex, in addition to being able to pre-record his radio show in 1948 for the American Broadcasting Company with an Ampex 200 tape recorder costing over $5,000. This was at a time when an American could buy a new car for under $2,000.

Ampex tape machines first displaced disc transcription companies, which had recorded low numbers of high fidelity discs intended solely for radio broadcast. But probably a little before 1950, the machines began finding their way into recording studios of the phonograph record industry – both because prices were coming down dramatically and because of continuing advances in fidelity.

There is amazingly little information available on just when the major record companies transitioned from wax discs to magnetic tape, but it is clear that the process had largely been completed by 1954, when a young Elvis Presley made his first recording on an Ampex tape recorder at a backwater studio in Memphis, Tennessee called Sun Records. The recording giants like RCA Victor and Columbia began using the Ampex machines, but seem to have done so without much fanfare – probably because they had nothing to do with developing the technology. They would be quite vocal about the long play record formats which they did develop.

A footnote to this story is that in 1946, the Magnecord Corporation attempted to adapt wire recording technology to recording studios. That effort lasted about a year after it became clear that magnetic tape had leapfrogged steel wire as a superior medium for high fidelity sound recordings. Ampex recorders using 3M tape consigned the wire recorder to the dustbin almost immediately.

The combination of far higher sound fidelity and recording times unhampered by the old three or five minute constraints of wax discs literally changed everything in how music was recorded. It was very soon that Ampex was at work on multi-track recording which resulted in stereo and in advanced abilities to mix and balance those tracks for a final product. Who would have imagined that we would have Nazi Germany and Bing Crosby to thank for the music we all grew up with?

I love the story of tape. Great overview here, but lots of nuance and minutia to discover. The Germans, of course, were running headlong into developing and improving the magnetic tape industry so that Hitlers speeches could be rebroadcast, that was the main driver. The German recording industry also has a massive library of recorded sound all the way back to Edison cylinders, covering exotic and esoteric cultures and music. There are great stories about “sound catchers” still using small Edison cylinder recorders in rural and deep jungle areas because wire, tape, and disc recorders were unmanageable in size and power needs.

It’s amazing to me that Ampex was such a key player in the development of tape recording in America and the world, and yet, when you read those stories about vintage master tapes that need to be actually “baked” in an oven before they can be played once, because the binder was such garbage it was shedding the magnetic media, you find out the tapes were inevitably a series of Ampex tapes from a certain era. There are stories of Scotch professional recording tapes from the same eras, being pristine and in perfect condition! No “baking” needed. Recently read some stories about some late ‘50’s-early ‘60’s jazz masters discovered recorded on Scotch that are in perfect shape with no shedding at all.

I still wish I could find a reasonable priced stereo Nagra portable tape recorder. I have two different brand digital recorders for some sound recording I do for interviews and documentaries, and they each work entirely different, and I have to reread the manuals before I can even use them, plus I can’t “ride” the audio input on either of them. I was doin way better with tape back in the day!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, this story could fill about a month of posts if we went down the bigger rabbit holes.

I was amazed at how little information is out there on when the big record companies made the transition from wax discs to tape. RCA and Columbia were not remotely shy about trumpeting their scientific skills when long-play discs came out, but then “not invented here” syndrome is definitely a thing.

Also, Ampex kind of bumbled into this market and did not have the kind of engineering pedigree that 3M had. I wonder if those tapes you mention were made by Ampex or supplied by some nameless 3rd party.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, that was super interesting. I’m quite happy that I have access to tape recorded music and am not being forced to listen to Hitler’s recorded speeches in 2024.

This reminds me of James Burke’s BBC documentaries (still highly recommended if you haven’t watched them) one of his big points was that major breakthroughs in technology were usually incremental improvements of an idea by different people, which is certainly the case here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Doug, plus one for James Burke! My local PBS channel played his BBC series Connections in the late 70’s, and I was riveted. I had the corresponding book until just a few years ago when I was divesting myself of a lot of stuff. It was great to page though every once and a while!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if Hitler speeches would be easier to take for those of us who don’t speak German.

And I have not yet seen those shows. I think the Germans did much of the heavy lifting here.

LikeLike

Terrific article. Technology, and technological advances, are amazing. The people behind all of that are something else.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed, and thanks! Some inventions make me think “why didn’t someone think of this sooner.” Magnetic tape is not one of those inventions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating to read the explanation. To me it all seems just as impossible as ocean liners floating, airplanes flying, and images coming coming through my television box, no matter how many times these magical things are explained to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, right? I kind of understand a needle in a groove. But magnetic tape is just magic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting how many things had to happen to get us to where we are now!

My husband bought me wireless earbuds for Christmas and it is fascinating to listen to songs I thought I knew – but in a far superior way! The complex blend of vocals and instruments is delivered in a far better way than I have ever heard the music before!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have yet to try wireless earbuds, and you are giving me another nudge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! This was really cool. You always dig up interesting story ideas. When I first started collecting Old Time Radio Shows on cassette tapes they always had the same announcement, “This old time radio show was originally aired live, long before the advent of high fidelity. As a result you may hear an occasional surface noise or volume drop, so common to old radio. We hope, however, that that won’t take away from your pleasure in listening to this, one of the all time favorite shows.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Without researching, I believe that most of the old radio shows we can access today were captured on discs from the live broadcast by one of the transcription disc companies. They would press a small number of low rpm soft acetate (for low surface noise) discs for rebroadcast as reruns. I’m glad they did so! And it would have been so much easier with tape.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those interested in the history of recording music and cultures, should strive to find a book called Song Catchers, In Search of the Worlds Music, by the great Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead. JP’a entry here reminded me of how much I loved that book and I’m glad I have it. They also have reference to the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, which has a large collection of cultural music and spoken word recordings from all eras from Edison cylinders to disc cutters and wire recordings! Wiki it up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds really interesting!

LikeLike

Very interesting post JP. We take a lot for granted these days when we listen to music, never thinking of the thought process that originally created the means to record music the way it once was done.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We don’t always want to look behind the curtain at how things are made (like hot dogs or sausage) but I am fascinated by obsolete tech.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the scratchiness of the tape tells us how old a recording is sometimes … that always amazes me as to the tinny sounds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got stuck on the RCA Victor video – couldn’t stop watching. What a fascinating look back in time. For one, I can’t imagine the extent of engineering behind the manufacturing process, evident because I lost track of the dozens of steps involved. I pictured some off-camera poster board list of steps, so the line workers knew which chemical bath came next. I also got a kick out of the dress code (ties on all of the men except those who worked the giant shellac machine), and how the finishing and packaging seemed reserved for women. Had to smile when they showed the final product playing. Even if the music sounded clear and even, the label was not perfectly centered, giving the impression of a wobbly disc. Of course, we’re talking about manufacturing from almost a hundred years ago. They can be forgiven for a little slop in the process.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there was so much hand work required in the process with each individual disc being handled multiple times. Which is probably why they were relatively expensive. A 35 cent record in 1946 would cost about $5.50 today – just for one hit song and a flip side.

And did you notice that fancy (and expensive) record changing machine in those peoples’ living room?

LikeLiked by 1 person

$5.50 is a lot more than what I think I paid for 45s in the 1970s (surely less than a dollar each). By then I’m sure the manufacturing process was streamlined and automated. And yes, a fancy record player for a perfect-looking family. Didn’t you write about those devices too (and how they had a short lifespan) or am I confusing the product with something else?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I did touch on them, possibly in the piece I did on the development of the long play record.

LikeLike