Phil Harris – More Than Just Your (Above) Average Bear

Did you know that the most famous bear in the world came from Linton, Indiana? Well now you do. OK, maybe Baloo the Bear from Disney’s 1967 animated film The Jungle Book is not a real bear, but he is certainly famous – owing in no small part to the guy who gave him his voice and his personality: Phil Harris. Harris is well along the fade into obscurity suffered by most entertainers of his era, but is one who deserves to be remembered for a remarkable entertainment career that spanned over seventy years and almost every entertainment medium you can think of.

Most of my posts about jazz musicians is about the music that keeps those long-gone entertainers alive in recorded performances. This one is a little different because Phil Harris, though a musician, wasn’t so much memorable for his musicianship as for a personality that could not be contained within the role of band leader.

Born in Linton, Indiana on June 24, 1904, Wonga Phillip Harris (yes, Wonga was his real name) was the son of vaudeville performers who taught him to play musical instruments at a young age. He preferred the drums and by the age of 9 he was playing drums and doing sound effects in a local theater. His family moved to Nashville, Tennessee around 1910 where his father led a circus band that employed young Phil as a drummer.

Harris got hired by the Francis Craig band – a local Nashville outfit that gave some other notables a first break, including Dinah Shore. In the 5 or 6 years leading up to 1929, Harris’ talents led him throughout the south heading his own Dixie Syncopators and then Henry Halstead’s California-based band (where he played with jazz trumpeter Red Nichols). Around 1929 he teamed with co-leader Carol Lofner to form the Lofner-Harris Orchestra, where Phil was both singer/front man and drummer at a long-term gig at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel.

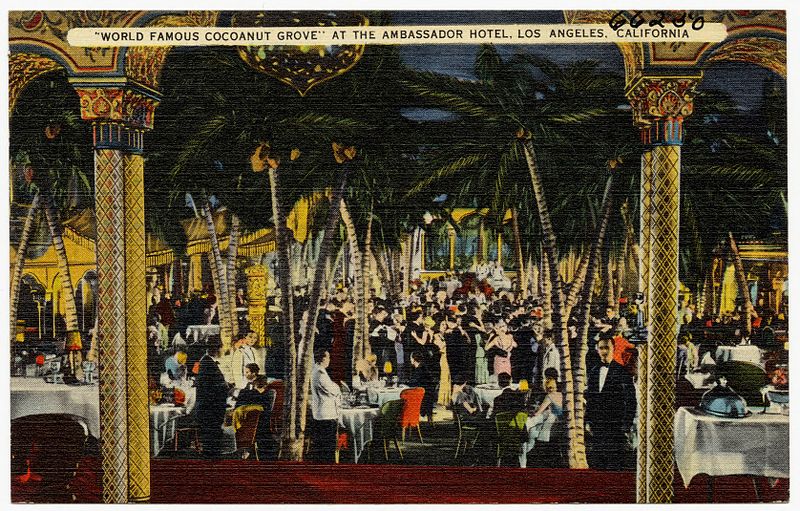

Harris may have been pretty good on drums, but that was not his main talent. What got him noticed was his inimitable vocal style and personality that kept the band employed in San Francisco through the rough early years of the Depression. And when he and his partner broke up, it was either luck or instinct that got Harris down to Los Angeles where he formed a new band and got hired in 1932 as the featured entertainment for The Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel.

The Ambassador and its nightclub was one of THE places to be in the early 1930s, and if there was anyplace where a guy with a big personality was to get noticed, it would have been right where he landed. From 1932 to 1936 Phil Harris and his Cocoanut Grove Orchestra entertained the big names of Hollywood and got plenty of exposure on records.

Musically, Harris’ band occupies an odd spot. It did not cater to jazz tastes but was also far from a normal “hotel band”. It was a solid musical outfit but was built more for entertaining “in crowd” dancers than for straight jazz. And after his earliest days at the Ambassador, he never had the financial need for constant touring and recording as most other bands had. All that aside, the one thing that set his outfit aside was his vocal delivery. This 1932 recording of Minnie the Mermaid is an example. Musically, it was neither ahead of or behind its era, but was a showcase for Phil’s unique way of putting a song across with a persona he would cultivate over the next several decades.

Harris’ Los Angeles location kept him at the front of the style curve and by 1935 his band was swinging right there with Benny Goodman. Only instead of featuring the instruments, the band remained a strong foundation for Harris’ half-spoken and half-sung vocal treatment with that unique voice. I’d Love To Take Orders From You demonstrates a tight, first rate swing band and a singer with a style like nobody else. If you can’t get enough of Phil’s music of the 30’s, Too Marvelous For Words from 1937 is another great example.

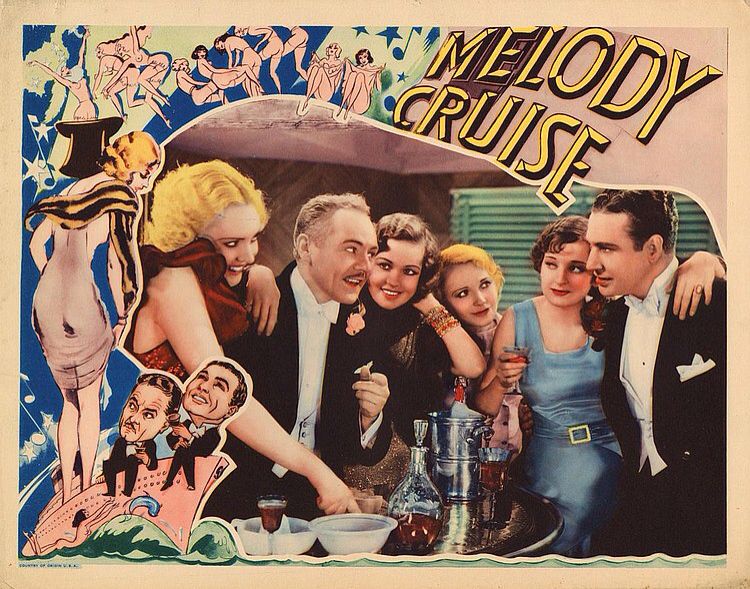

These discussions of Harris’ records of the 1930s are interesting but not really the main point of his career. After an uncredited role as a drummer in 1929, Harris was in two films released in the summer of 1933 – a feature called Melody Cruise (in which he co-starred with Charlie Ruggles) and an RKO comedy short called So This Is Harris. The second won the academy award for best live-action comedy short that year and is as good an example as any of the kind of sly, risque subjects that led to the implementation of Hollywood’s production code a couple of years later. With a famous orchestra and an award-winning movie appearance under his belt, what was left? The answer (in 1936) was radio.

That year, comedian Jack Benny’s Jell-O radio program was looking for a band/music director and Harris got the job. Jack saw quickly that Phil was unusually adept at snappy one-liners and the show’s writers soon made him a regular character – a hard drinking, womanizing, southern hipster who was blissfully ignorant about almost everything.

“Hi-ya Jackson!” was his blustery greeting for Benny in the program before the dialog would bounce back and forth with Jack and Phil making jokes at each other’s expense in a show that may have been the high water mark of network radio. The show might have been the original workplace sitcom with all of the characters being exaggerations of the stars who played them. Harris remained a regular on the Benny show (with a 1942-45 break in which he and his entire band joined the service) until 1952.

The years after WWII saw Harris take command of almost every entertainment medium there was. In addition to his regular spot with Benny he began churning out a series of hit records and also continued in a series of film roles. In 1945’s I Love A Bandleader, he starred (with his Jack Benny cast-mate Eddie “Rochester” Anderson) as an unassuming painter who gets hit in the head and wakes up thinking that he is a bandleader. And in 1946 his popularity spawned a spin-off radio show of his own that ran right after Benny’s Sunday evening time slot for the next 8 years. What had begun as the Fitch Bandwagon in 1938 eventually became a family sitcom called the Phil Harris-Alice Faye show which ran until 1954. Faye, incidentally, was the former film star who was Harris’ real-life wife in a marriage that would last from 1941 until Phil’s 1995 death.

It is hard to get an appreciation of Harris at the peak of his fame without listening to the old radio shows which were his bread and butter for over fifteen years, but here is a 2 minute clip of a fairly typical exchange between Harris and Jack Benny. This is from an episode of The Phil Harris – Alice Faye Show where the plot involved whether Jack Benny was going to renew Phil’s contract on Jack’s show. Of course, the main gag through the episode was Benny, whose persona was every bit as cheap and stingy as Harris’ character was stupid. There are hours and hours of both of those shows available online and let me tell you, they can be addictive.

Harris’ postwar recording output was mainly a series of novelty numbers like his signature tune, That’s What I Like About The South. He recorded this one three times – I like this 1945 version on the independent ARA label the best – if you listen behind Phil there is a jazz guitarist having a ball. This was an update to a 1937 version that is slower and not as fun, and a 1947 re-recording of this version for RCA Victor which has less guitar and more piano. The number was also featured in I Love a Bandleader if you feel like watching rather than just listening.

Harris’ recording peak was undoubtedly his million-selling novelty hit The Thing from 1950, but I prefer this lesser known B side from 1947 – Some Little Bug Is Going To Find You. Maybe it is Covid-fatigue, but I am kind of liking Ol’ Curley’s attitude in this one.

Some of Harris’ record titles of that era are problematic to modern sensibilities. At first blush, a record like The Darktown Poker Club should make us run away from Harris’ legacy as fast as we can. But a little research turned up that this was one of at least three Harris covers of records made famous by Bert Williams before 1920. Williams was the original black superstar in the days of vaudeville and Harris was clearly a fan of Williams’ popular comedic records, which had been huge sellers in their day. Woodman, Spare That Tree (1913), The Darktown Poker Club (1914), and Somebody Else, Not Me (1919) were each modernized and covered by Harris multiple times between 1937 and 1947.

As an aside, at least one writer* noted that especially after WWII, Phil Harris’ character on Jack Benny’s radio show exhibited many of the old stereotypes normally attributed to black characters (an uneducated and ignorant southerner, a jive-talking, flashy dresser who lived to gamble and drink) in ways that allowed the real black cast member (Eddie “Rochester” Anderson) to avoid most of them. I think the fair conclusion is that Harris held an affinity for Bert Williams and that he adapted more than a little of the old vaudevillian’s work to his modern radio persona. And other than its title (which has been changed to Downtown or Uptown Poker Club by some later performers) the record is just blustery old Phil as a kind of a rustic rube who is tired of getting cheated.

Phil Harris undoubtedly could have made a success in television after his radio show ended in 1954 but he apparently did not see the need, having a full and happy life with a steady stream of guest-star gigs on TV in addition to several movie roles and golf. There was lots and lots of golf.

It seemed that his A List days might have been behind Harris in the mid 1960’s when he got a call from the Disney studios, asking if he would like to do the voice for Baloo the Bear in a new movie that would turn out to be the last one fully under Walt Disney’s creative control. Walt Disney had met Harris at a party and thought he would be perfect for the role of Baloo in The Jungle Book – an opinion not shared by most of Disney’s writers, it seems. When Harris got the script it didn’t feel right to him and he went rogue, ad libbing many of his lines – a skill he had perfected during his long radio career. Some sources say that the writers re-did virtually the entire script after Phil came on the job, so as to re-orient dialog to the personalities of the voice actors who brought the characters to the screen. And wasn’t his Baloo the best part about the entire movie? Whether you agree or not, Phil Harris’ Baloo undeniably marked a change in how Disney’s animated characters were voiced – is there a single subsequent Disney movie that did not follow his style?

Harris would spend much of the rest of his life doing voice work, following up as O’Malley the alley cat in 1970’s The Aristocats and as Little John in 1973’s Robin Hood. His last professional credit was in the role of Patou, the bassett hound and narrator for the 1991 film Rock-A-Doodle, based on the tale of Chanticler. Harris died just three years after that film was released, at the age of 91.

Was there anyone else like Phil Harris? Or was Phil Harris like anyone else? There are others who got their start in music and became well known dramatic or comedic performers – Let’s see, Bobby Troupe and Julie London became a doctor and a nurse on television’s Emergency, and rapper Ice T became a TV detective. So maybe Phil Harris going from band drummer to radio, movies and TV (playing roles from blustery bandleader to bear to bassett hound) isn’t all that unusual. His records also inspired later performers (mostly country – Jerry Reed comes to mind) who took several of his “talking songs” to later audiences. And even later in his career he continued doing straight music, including this lovely tune from 1968 that would become much better known when Frank Sinatra covered it in his 1981 album She Shot Me Down.

By all accounts Phil Harris was a soft spoken guy who was generous to those around him – and especially generous to Linton, Indiana, to which he lent a lot of support later in his life. Phil Harris was living proof that a musician with a quick wit and a southern drawl could go a long way from a little coal mining town in Indiana to hit the top rungs in records, radio, movies and television. He was a lot more than just your average bear.

* Michele Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952 (University of Minnesota Press, 1997)

Media Credits:

Musical selections: As identified in the YouTube pages embedded herein.

Photo Credits:

Featured photo – c. 1936 promotional photo of Phil Harris at an NBC microphone, cropped for size

Opening photo – Album cover from the sound track of Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book via Cartoonresearch.com

Undated autographed publicity photo of Phil Harris as offered for sale at regisautographs.com

Mid 1920’s photograph of the Henry Halstead Orchestra, including Phil Harris and Red Nichols via syncopatedtimes.com

Postcard featuring the exterior of Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles c. 1920’s as offered for sale at postcardshopping.com

Postcard featuring the interior of the Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles c. 1930s via digitalcommonwealth.org

Publicity artwork for the 1933 RKO Radio Pictures production Melody Cruise

Pre-1949 photo of the cast of The Jack Benny Program via a random Pinterest page

Publicity photo of Phil Harris and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson for the 1945 Columbia Pictures production I Love A Bandleader

c. 1911 photograph of Bert Williams from the New York Public Library via newyorktheater.me

c. 1950 Publicity photo of l-r Phil Harris, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson and Jack Benny in a Maxwell automobile at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway via askmen.com

c. 1949 cover of Radio & Television Mirror Magazine featuring Phil Harris and Alice Faye, via tralfaz.blogspot.com

c. 1964 photo of Sebastian Cabot, Sterling Holloway and Phil Harris during production of Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book via the Flickr page of Tom Simpson, with CC2.0 license.

c. 1990 autographed photo of Phil Harris and Alice Faye, as offered for sale on historyforsale.com

Wild entry! I know something of Phil Harris from early TV reruns and voice-overs, but virtually nothing about his musical accomplishments or status! Whata great back story. I’ll have to listen to all when I have more time! Another great musical history entry!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I stumbled across one of his records from the 30s and remembered how someone had once told me that he once had a first rate band. I couldn’t see it at the time, which was before his old stuff was readily available online.

I started out to feature his music and got sucked into the enormity of his entertainment career. The nearly 20 years in network radio was completely unknown to me – I had known he had done some radio work but not the scale and duration of it.

LikeLike

I’d actually looked some stuff up on Phil Harris a few years ago, because I was wondering who did the voice of Baloo. I had been thinking it was Hoyt Axton.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hoyt Axton – now there is a name I have not heard in a long time. I remember him in the 70s, so he was surely around before that. I need to look him up.

LikeLike

At some point shortly after 1976, Disney must have re-released The Jungle Book as I vividly remember seeing it in the theatre. For four- or five-year old me, there was Baloo and then the rest of the movie.

Thank you for this. I will be listening to all of these audio / video clips and knew nothing about Phil Harris prior to reading this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Somehow I did not see The Jungle Book when it came out. I would have been in the prime demographic, so I have no answer to how that never happened. But I knew about it and saw it some years later when it came on television. And you stated it well – there was Baloo and then there was everyone else.

That whole radio era sunk into obscurity pretty quickly. Old movies were re-run on TV many times, as were old TV shows. But that 20 years of radio never saw the wide distribution to younger generations that movies and TV got, and have only recently become more widely available. So with Harris spending nearly 20 years (and gaining the peak of his fame) on radio and his later stuff being voice work where he himself went unseen, his descent into obscurity came fairly quickly.

I have been on a jag of listening to old radio shows after diving into Phil’s background and I have concluded that Lucille Ball’s early tv smash hit I Love Lucy was basically a recycling of the Phil Harris radio show concept – which was a family comedy about the life of a famous bandleader. Only in Lucy’s case, it was the wife who was the funny one and the bandleader husband who was the straight man. The comedy was different because of the different characters involved, of course, but I find the similarities interesting.

LikeLike

Interestingly enough, there used to be a public radio station near me that played old radio on Sunday night, and I used to fall asleep listening to it. Abruptly about a year ago, they pulled it off, no explanation unless you went to the web site, where they said the “stereo-types” on the programs were indefensible. I wrote them and vowed never to give them money again because that was over the top polly-anna-ism. They were highly entertaining, and everyone understood a private-eye calling a woman a “dame” was not correct today (or probably even then).

Anyway, to your point, I’m always amazed how some of my favorite radio programs, like “Yours truly, Johnny Dollar”, literally lasted until I was just about old enough to get my own transistor radio and listen! Then “poof” they were gone. I probably started to listen to British Invasion music about 1964, and YTJD was off the air in 1962. I have a pal about 7 years older than me, and he remembers listening to all those radio shows, like X-Minus One,, Johnny Dollar, etc. every night, and also remember when it just all changed to music, in like a second!

Still plenty of streamed old radio outlets, but not the same as lying in bed and listening to the “over the air” radio…

LikeLiked by 1 person

One that lasted a really long time was the CBS Radio Mystery Theater. It was still putting out new stuff in the mid 70s, hosted by EG Marshall. A local AM station ran it like 10 pm One night a week and I did exactly what you did, try to stay awake listening in bed with my headphones on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love Phil Harris. Our family has been long-time listeners of old-time radio and know a lot of him from that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have always found the old radio shows interesting and enjoyed the rare times when that kind of programming got exposure in later decades. I recall one summer in the early 70s when a local AM station devoted an hour of programming (maybe 7-8 pm) on weekday evenings to The Shadow and The Lone Ranger. Other times I have gotten exposure to Lum & Abner, The Great Gildersleeve and The Life of Riley. But overall I have not gone out of my way to amass collections of the stuff (which until recently had been the only way to get it in big batches).

I have been sucking up a lot of Jack Benny in the last couple of weeks and have noticed that a lot of the comedy relies on cultural references that might be tough translation for younger audiences. But I guess that is true with a lot of comedy as it ages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, context does help but a lot of jokes, especially in the older routines, are just funny. Who’s on First springs to mind and many of A&C’s bits. For quite a while one of the Christian radio stations played a couple of different episodes of shows after Adventures in Odyssey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was never a big Jungle Book fan but have to admit Baloo was the best part. I had to take my little brother to see it back in the 60’s when I was 11 and already too old for Disney cartoons, and then decades later I had to sit through it again with my nieces and nephew when they re-issued it. He sounds like an interesting guy….and that some bug is going to get you song is quite catchy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

During my teen and young adult years I can remember it being an item when he would appear at local celebrity golf events. I guess his Indiana connections made him open to coming back here to help raise money for charity events that involved golf. He sponsored an annual event in his hometown of Linton, Indiana for decades and the golf course there bears his name. I discovered that he donated his papers and memorabilia to the library there. Linton is less than a 90 minute drive from my house, so maybe that would be a worthwhile trip for me to make.

I remember hitting that age when Disney movies didn’t cut it anymore. I was still in the demographic for The Jungle Book (which, somehow, I did not see then) but was definitely beyond it soon after. I did not see The Aristocats until my own kids were young.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Old Time Radio, streamed from Antioch Illinois, about 60 miles away from me….

https://radio.macinmind.com/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating and diverse career. After listening to the Harris-Faye clip with Jack Benny I can see how the comedic style would be addicting. The humor was refreshingly innocent back then. And when Harris’s voice goes bass I hear Baloo. I couldn’t hear him when I was first reading, because I kept hearing King Louie the ape instead (who sounded very much like Louis Armstrong). Sebastian Cabot, whoa – talk about a throwback. I only remember him from the show Family Affair, as the butler of widower Brian Keith trying to raise two kids. Finally, I hope you’ll do a piece on Radio Mystery Theater, JP. That show is forever linked to the late Sunday nights of my youth. I can still hear the intro, when the creaky door opens and the moaning wind passes through. I need to look up a few of those shows.

LikeLiked by 1 person

King Louis was voiced by Louis Prima, who was a singer/musician/real character (kind of) popular in the 50s. And I watched a lot of Family Affair, as it was in perpetual summer reruns when we were home from school. “Uncle Beeeel, Uncle Beeeel”

The old radio comedy was both more innocent and also more willing to make fun of people. Don Wilson, the announcer, withstood a lot of fat jokes over the decades. Like when the group gets off a train and the porter asks if the men would like to have their suits brushed off. The guy does Jack and Phil (with the wisk wisk sound of brushing fabric) for maybe 6 or 8 wisks each. Then they do Don, and the wisking goes on seemingly forever as the audience laughs, until it finally stops and the porter asks him to turn around so he can get his back. But then everyone got his/her turn at being the butt of the jokes – Jack was vain and cheap, Phil was dumb and a hard partier, and so on. I think everyone had thicker skin back then – they had lived through some pretty rough stuff (a depression and a couple of world wars) so what was the harm in a joke?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. I miss the kind of humor where the audience could just take a breath and not worry about anyone around them being offended.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Peggy Lee & Dave Barbour, A Happy Couple Making Beautiful Music Together. Literally. | J. P.'s Blog