The Swinging Life – 1936 Style

Every generation has had “The One”. That one musical artist (or group) that changed popular music for a generation. And that made that generation’s elders fret that the aggressive and subversive new music that the kids were listening to was further evidence of the world going to Hell in a handbasket. Elvis Presley was “The One” in the 1950s and The Beatles did the same thing a decade later. There was “The One” in the 1930s as well, and his name was Benny Goodman.

Before he became “The King of Swing”, Benny Goodman was a jewish kid who grew up dirt poor in Chicago. He took lessons on a clarinet and, with the kind of drive and determination seldom found in those who ate regularly, came to command the instrument. He eventually found his way into the thriving jazz scene that was Chicago in the 1920s.

Popular lore has Goodman bursting onto the scene about 1934 with this new music called “Swing”. As with most popular lore, there is a touch of truth to it but not much more.

A transition from one musical style to another doesn’t usually just burst onto the scene. Instead it incubates, grows and sputters its way to prominence. Just as rhythm and blues would morph into rock and roll in the ’50s, so would the jazz of the 1920s transform itself into the swing of the 1930s. There was a time when the essence of swing would need no explanation, but I fear that time has passed. Up until the very early 1930s jazz had a very bouncy, evenly spaced rhythm that emphasized the first beat, sort of a ONE two ONE two ONE two ONE two. (Like this record by McKinney’s Cotton Pickers from 1929).

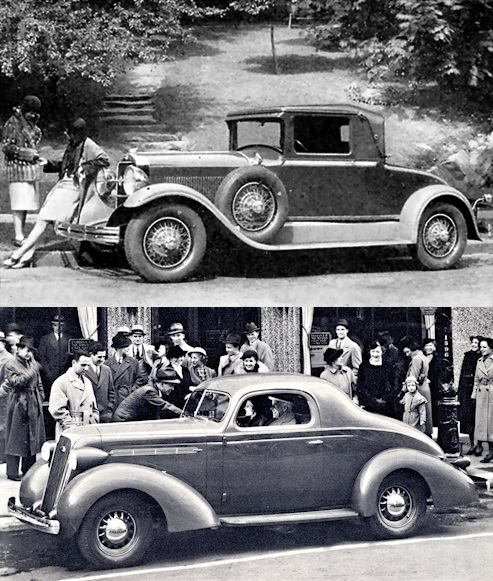

1929 (top) and 1936 (bottom) Studebaker coupes

Swing sort of smoothed out the bounce by stretching out the fist note a bit and shortening the second, or more of a Dahh da Dahh da Dahh da Dahh da. The effect was to give the music more of a sensation of pulse or forward motion as opposed to an up and down bounce. I suppose that we could think of it as a kind of streamlining. Just as automobiles and trains went from boxy in 1929 to streamlined by 1935-36, music did too – and they called it swing. I think that a listen to Swingtime In The Rockies will illustrate it pretty well.

If you spend any time listening to music from that transition period from about, say, 1927-1934, you will learn one thing: that the black bands of that segregated era were working into a swing beat a lot earlier than the white bands did. Musicians like Fletcher Henderson were pushing the stylistic envelope while their white counterparts (with some exceptions) were not as adventurous.

Benny Goodman didn’t invent swing, but what he did do was come along at the right time and make it popular with the majority of young listeners and dancers. Today some might call this Cultural Appropriation, and there could something to that. On the flip side, the new popularity of the black bands’ stock in trade helped those bands and their alumnae towards a much wider audience than they might have enjoyed otherwise.

It almost didn’t happen. In 1934 Goodman had gotten signed to a Saturday evening national radio program called Let’s Dance. The show began at 10:30 pm in the Eastern time zone, which meant that Goodman’s final hour segment did not begin until the wee hours of Sunday morning. The result of the network’s scheduling was a fan base much heavier on the west coast.

Goodman had hired Fletcher Henderson (who had disbanded because of the Depression) to write music and even bought the “book” of arrangements that Henderson’s band had played. The result was a band that was a real contrast to the more conventional orchestras which occupied the earlier parts of the show. After the show ended in the spring of 1935 the Goodman band started a coast to coast tour. But things did not go well.

One reason was that he was not playing what was popular in the summer of 1935, at least not the stuff commonly played by white bands for white audiences. What was popular? Stuff like this by Ozzie Nelson. Or this by Paul Whiteman.

Goodman’s crowds were small and unenthusiastic, a scene that was replayed night after night as they slogged across the country. When they finally hit Los Angeles the decision had already been made to throw in the towel. But, Goodman decided, if they were finished anyhow, they were going to go out playing what they wanted to play.

Much to the band’s surprise the crowd at that first gig in LA went wild. Little did Goodman know that those west coast fans had been buying and dancing to his records all summer and were really jazzed up when the band made its appearance.

Swingtime In The Rockies was recorded in 1936, which marked the second year of the twenty-six year old Goodman’s newfound superstardom. The song was written by Jimmy Mundy, another of the black musicians and arrangers that Goodman kept in his orbit.

The mystery of these early Goodman records is the way he blended at least most of the the loose, free-swinging feel of the black jazz bands with his demand for precision. The result was music that did two things at once: it had a serious swing to it and it was executed absolutely perfectly.

If you want to compare this to another 1936 record that we have featured (Count Basie’s Shinin’ Shoes) you will notice one big difference. Basie’s music was looser, made up of almost nothing but improvised solos while Benny Goodman’s music of the same time was primarily a written arrangement with some short solos added for a little spice.

From the very beginning and even at this very fast tempo, the saxophones are together, the brass is together, the rhythm is together, and there is not a stray or off note to be heard anywhere. Because Benny Goodman commanded it.

The style has been described as a call and response, something reminiscent of the worship tradition in the black churches of the time. One section calls out and another section answers.

Early swing music like Goodman’s had a heavier rhythm section than later bands would have. Gene Krupa was the drummer who became famous along with Goodman and whose big pulsing bass drum was a constant in all but the quietest passages of these early Goodman recordings. The identity of the trumpet soloist is a mystery. Although it sounds like Harry James (another star launched by the Goodman band) all information indicates that James did not join the band until the following year. My next guess would be Chris Griffin who, along with James and Ziggy Elman would make up Goodman’s 1937-38 trumpet section, his most famous.

Benny himself was one of the great jazz clarinet players. Jazz fans have argued for decades about who was better, Goodman or Artie Shaw. But to put the argument in terms that moderns can understand, this was like arguing whether Mercedes or BMW is the best German car. For me, I think that while Shaw may have been more musically adventurous, Goodman’s style had a way of joyfully soaring above whatever else the band may have been doing. There is just a sense of fun and happiness to these early Goodman records that is hard to beat. Is there a particular kind of music that is almost guaranteed to improve your mood? For me, this is it.

After 1938 tastes seemed to move on and Benny Goodman had a hard time moving on with them. His dictatorial style was not good for keeping talent and he was not disposed to experimentation as musical trends moved to more modern styles. He had another burst of popularity in the early ’40s but after that spent the rest of his long career revisiting those hits from the mid 1930s. He continued to perform until shortly before his death in 1986.

It is my belief that Rock and roll would have come without Elvis and the British Invasion would have happened without the Beatles. And in the same way, Swing would have come along without Benny Goodman. But aren’t we better off that they were all here? If you click the link in that second picture and listen to Swingtime In The Rockies a time or three, I think you will agree.

Your music posts are my favorite. More please! I am at least lightly familiar with almost all of the artists you profile (thanks to my grandparents, who knew all the music of their generation) but don’t know much about the artists themselves.

LikeLike

Well, thank you. I always find the music more interesting when I know some context and I hope others might too.

LikeLike

+1, I was guessing it would be food today but it’s music. Ed Stembridge has me on a bit of a Western Swing guitar kick this week, so this’ll fit right in…

LikeLike

I have not listened to enough Western Swing guitar. I need to do something about that.

LikeLike

You should, then let us know what you find out.

Ed’s listening to the Quebe (Kway-bee?) sisters: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-H24HFte3iE

And I’m listening to The Bebop Cowboys: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnGI7Z991vc

LikeLike

Ha, some good lunchtime listening! The Bebop Cowboys are particularly fun, proving that everything old is new again. Theirs is an inventive and fun turnabout on the song made famous by Phil Harris (originally from Linton, Indiana, by the way) in the 40s called That’s What I Like About The South. You might recognize the voice from his roles in Disney’s original Jungle Book and The Aristocats. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JeLy8C-g27Y

LikeLike

I would just like to thank JP, Doug, Ed & YouTube for ruining what was left of my productivity tonight. 🙂

Those are some excellent musical holes to fall down.

LikeLike

Aren’t they? And I only let those other two spoil my productivity over lunch. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: A Sweetie By Jean Goldkette – A Sample From The Jazz Age | J. P. Cavanaugh's Blog

80 year anniversary 6 minute piece on NPR:

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/16/578312844/how-benny-goodman-orchestrated-the-most-important-concert-in-jazz-history

LikeLike

A very nice addition, R L. I have had selected cuts from that concert that got onto LPs in the 70s and got the entire concert on CD about 10 years ago. Definitely groundbreaking!

LikeLike

Somewhere in my youth I heard parts of the 1938 concert (perhaps my parents had the LP) and Sing Sing Sing was a wonder to my marching band and orchestra B-flat clarinet playing self.

Over the years radio stations would play that song, but it never sounded “right”, either limited to the first part, or worse, not from the actual concert.

The best way to tell the real from the fake was, if it have Jeff Stacy’s solo.

Then 10 or more years ago I got the two CDs made from that single overhead microphone, and reveled in the full event, static and recording noise and all.

I’m not sufficiently knowledgeable to wax eloquent about jazz piano, but Jeff Stacy’s unplanned and unexpected (by him and everyone else) solo at the very end of the main concert was otherworldly. During this solo, he only connection to the concert was Gene Kupa’s faint but steady heartbeat. To fully appreciate Stacy’s solo one needs to hear what came before it in the hall that night, but here’s a link to that solo, starting with Goodman’s high C, and then getting back to earth with cow bells and Krupa’s machine gun.

LikeLike

Yes, that is one that is implanted deeply in my brain. It is unusual too because Goodman’s band did not usually make much room for piano solos. Such a contrast from, say, Basie where that piano was a feature.

LikeLike

Pingback: Battle Of The Bands – Miller vs. Goodman and Two Strings Of Pearls | J. P.'s Blog

Pingback: Rose Room By The Benny Goodman Sextet – Meet Charlie Christian And His E-Lectric Guitar | J. P.'s Blog

Pingback: Rex Stewart Goes All Zaza – Which Is Good | J. P.'s Blog

Pingback: The Boswell Sisters (or How Three Little Girls From New Orleans Changed Popular Jazz Singing) | J. P.'s Blog